A pleasant, somewhat lazy, couple of weeks <working> in Hong Kong and Shenzhen. Sitting on a surprisingly pleasant Shenzhen beach this week I watched the Hong Kong tycoon fraternity make its school trip to Beijing. Led by Head Boy Li Ka-shing, it was a full court press. Senior prefects Lee Shau-kee and Robert Kuok kept good order, while the dim but dependable Tung Chee-hwa explained his love of games and recited a short Ode to the Celestial Throne before the assembled Chinese leadership. A tremendous time was had by all, with the boys remarking that carpet and decor quality in the Great Hall is now almost as good as at home.

On the street of course, things are not quite so happy.

While the sixth form of St. Swag’s was up in Beijing learning how all is well in Hong Kong as is, school kids in the Special Administrative Region are boycotting classes this week to protest China’s gerrymandering of the 2017 election arrangements. If you haven’t followed it, the game is that everyone in Hong Kong will get a vote (as promised in the Basic Law), but Beijing will choose the candidates (<two or three>). It is actually a step back from the current arrangements which at least allowed the election of Henry Tang to Chief Executive to be blocked, replaced instead by the ineffectual but more brain-functional CY Leung.

Hong Kong, though it is rarely stated, is now just like Taiwan. The Taiwanese call it <Three Thirds>. In Taiwan, one third is Deep Blue (older, KMT, pro mainland integration). One third is Deep Green (younger, Democratic Progressive Party, pro independence). One third is in the middle.

So too, with only modest variation, in Hong Kong. There is no explicit pro independence camp but the generational gap is just the same. Hong Kong, like Taiwan, has entered its 1960s. And in the 1960s students on campus get beaten, and even shot if you remember, in their fight for what is right.

If you care at all, it is time to do whatever you can to prevent violence from arriving. You might write to the Chinese. But if you are a gweilo, that is likely counter-productive. Better to write to the American and British consuls in Hong Kong (emails below), and to the British and American governments, urging them to stand up for the spirit as well as the letter of the Basic Law, and to be ready to grant visas to Hong Kong students who will get arrest records, even criminal convictions, for peacefully protesting Beijing’s behaviour. It does make a difference if you have a moment.

Meanwhile, the Emperor. At the same time it is gently screwing Hong Kong, the Xi Jinping government’s decision to give a life sentence to, and seize all the assets of, the leading, non-separatist voice of Uighur nationalism, Ilham Tohti, is surely the most horrible, colonial, racist act we have seen from China for a very long time. Obama may have a lot on the Middle East, but he needs to draw some lines in the sand in East Asia. There are still plenty of rational voices in China, like there were in 1920s Japan. But the longer this stuff goes on, the harder, I think, the negotiating process becomes. I do not want to read this blog entry in 10 years time and find that some very unpleasant historical analogies going through my head were justified.

Well, enough of the misery. Tomorrow I return to Hong Kong for dinner with dear Hemlock. Back when CY Leung was elected, Hemlock had a hard-on for him, said he was going to change stuff. Not so much on the democratisation front, which would have to occur through a degree of managed confrontation, but in terms of the godfather economy and all those stitch-up oligopolies in real estate and retail and the securities markets. You gotta love Hemlock, even if he’s not as funny as he used to be. It is so heartening that after all these decades, the old boy could still be an ingenue (accent missing). It is so strange that it should turn out that I am the cynical one.

Above: Can’t get a bigger photo. Running anti-clockwise from Xi Jin-ping on the right, looks to me like Tung, K.S., Lee Shau-kee, Robert Kuok, Henry Cheng (son of Cheng Yu-tung, now decrepit), Lui, possibly Michael Kadoorie, and finally David Li of Bank of East Asia.

Saint Swag’s. September 2014 School trip to Beijing. 6th Form boys attending.

(Parents please note: the wearing of non-school uniform items such flat caps is strictly against school policy, including on school trips. Lui Senior (Cuthberts), who has already been in trouble this term for playing cards in dorm, has been fined a week’s tuck and given leaf sweeping for his transgression. This sort of thing will not be tolerated at St. Swag’s.)

Cheung Kong (Holdings) chairman Li Ka-shing

Chairman of Kerry Group, Robert Kuok

Chief executive officer of Shangri-La Asia, Kuok Khoon Chen

PCCW chairman and younger son of Li Ka-shing, Richard Li Tzar-kai

K Wah Group chairman and Galaxy Entertainment Group founder Lui Che-woo

Henderson Land Development chairman Lee Shau-kee and his elder son Peter Lee Ka-kit

Sun Hung Kai Properties Alternate Director Adam Kwok Kai-fai

Bank of East Asia chairman David Li Kwok-po

New World Development chairman Henry Cheng Kar-shun

CLP Holdings chairman Michael Kadoorie

Sino Land chairman Robert Ng Chee Siong

Harilela Group vice-chairman Gary Harilela

Hang Lung Properties chairman Ronnie Chan Chichung

Shui On Land chairman Vincent Lo Hong-sui

MGM China’s co-chairman and daughter of casino mogul Stanley Ho Hung-sun, Pansy Ho Chiu-king

Ian Fok Chun-wan, son of the late Henry Fok Ying-tung

Wharf (Holdings) chairman Peter Woo Kwong-ching

Asia Financial Holdings chairman Robin Chan Yau-hing

Li & Fung honorary chairman Victor Fung Kwok-king

Lai Sun Development chairman Peter Lam Kin-ngok,

Oriental Press Group former chairman Ma Ching-kwan

Glorious Sun Enterprises chairman Yeung Chun-kam

Phoenix Satellite Television chairman Liu Changle

Swire Pacific director Ian Shiu Sai-cheung

Shimao Property Holdings founder and chairman Hui Wing-mau

China Grand Forestry Resources Group founder Ng Leung-ho

Goldlion Holdings deputy chairman Ricky Tsang Chi-ming

Novel Enterprises vice-chairman Ronald Chao Kee-young

HKR International managing director Victor Cha Mou-zing

Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation chief executive officer Peter Wong Tung-shun

Prof Anna Pao Sohmen, daughter of late tycoon Pao Yue-kong

Far East Consortium International chairman David Chiu Tat-cheong

Shun Hing Group vice-chairman David Mong Tak-yeung

Galaxy Entertainment Group deputy chairman Francis Lui Yiu-tung

Dah Sing Life Assurance Company chairman David Wong Shou-yeh

Far East Holdings International chairman Deacon Chiu’s son, Duncan Chiu

Bank of China International Holdings deputy chief executive officer Tse Yung-hoi

Sing Tao News Corporation chairman Charles Ho Tsu-kwok

More:

UK Consul General to write to about standing up for the Basic Law, granting visas, etc is Caroline Wilson. [email protected]

US Consul General to write to about standing up for the Basic Law (an agreement lodged with the United Nations), granting visas, etc is Clifford Hart. [email protected]

Why foreigners do have a dog in any Hong Kong fight. Re-posted NYT oped.

Op-ed about the Hong Kong situation by former Chinese political prisoners in the Wall Street Journal.

Video stream of Hong Kong student protests this week.

On why allowing everyone to vote but restricting the candidates isn’t democracy, Georgetown professor Don Clarke offers this nicely phrased US 3rd Circuit decision in a corporate voting case from 1985. Here’s the actual law library link (Durkin v National Bank of Olyphant). Of course what the Chinese are doing is just what British colonial governments did, but let’s not go there.

<We rest our holding as well on the common sense notion that the unadorned right to cast a ballot in a contest for office, a vehicle for participatory decisionmaking and the exercise of choice, is meaningless without the right to participate in selecting the contestants. As the nominating process circumscribes the range of the choice to be made, it is a fundamental and outcome-determinative step in the election of officeholders. To allow for voting while maintaining a closed candidate selection process thus renders the former an empty exercise. This is as true in the corporate suffrage contest as it is in civic elections, where federal law recognizes that access to the candidate selection process is a component of constitutionally-mandated voting rights.>

On Tohti:

Teng Biao writes in The Guardian that the guy sent down for life actually deserves the Nobel. Here is the background.

Nicholas Bequelin writes in the NYT that the treatment of Tohti will radicalise more Uighurs. This is your key piece of analysis.

English translation of Chang Ping article trying to find logic in the treatment of Ilham Tohti. See also the translated extracts from Tohti’s statement after sentencing, below.

Ilham Tohti’s statement after sentencing in Chinese. Here are some heart-rending extracts in English:

<My outcries are for our people and, even more, for the future of China.

Before entering prison, I kept worrying I wouldn’t be able to deal with the harshness inside. I worried I would betray my conscience, career, friends and family. I made it!

The upcoming life in prison is not something I’ve experienced, but it will nonetheless become our life and my experience. I don’t know how long my life can go on. I have courage; I will not be as fragile as that. If you hear news that I mutilated or killed myself, you can be certain it is made-up.

After seeing the judgment against me, contrary to what people may think, I now think I have a more important duty to bear.

Even though I have departed, I still live in anticipation of the sun and the future. I am convinced that China will become better, and that the constitutional rights of the Uighur people will, one day, be honored.

Peace is a heavenly gift to the Uighur and Han people. Only peace and good will can create a common interest.

I wear my shackles twenty-four hours a day, and was only allowed physical exercise for three hours out of eight months. My cell mates are eight sentenced Han prisoners. These are fairly harsh conditions. However, I count myself fortunate when I look at what has happened to my students and other Uighurs accused of separatist crimes. I had my own Han lawyer whom I appointed to defend me, and my family was allowed to attend my trial. I was able to say what I wanted to say. I hope that, through my case, rule of law in Xinjiang can improve, even if it is only a baby step.

After yesterday’s sentencing, I slept better than I ever did in the eight months (of my detention.) I never realized I had this in me. The only thing is don’t tell my old mother what happened. Tell my family to tell her that it’s only a five-year sentence. Last night, in the cell next door Parhat [student of Tohti’s] slammed himself against the door and cried out loud. I heard the sound of shackles, nonstop, as they were taken to interrogations. Maybe my students have been sentenced too.

(To his wife): My love, for the sake of our children, please be strong and don’t cry! In a future not too far away, we will be in each other’s arms once more. Take care of yourself! Love, Ilham.>

Only in Chinese on Hong Kong:

Wen Wei Po, Beijing mouthpiece in Hong Kong, says that Hong Kong student organiser Joshua Wong has received training from <black hands> in the US navy. I understand there is lots of this stuff doing the rounds in the official press.

Update, 29 September:

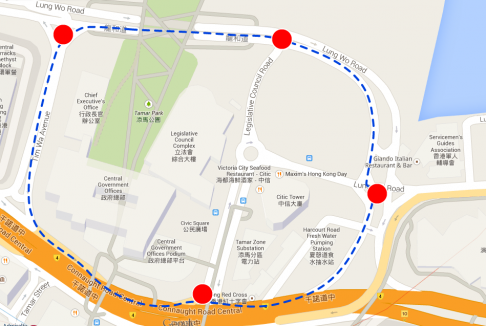

Well, it’s game on after a weekend of student-led confrontations with the police. Parts of HK island (Admiralty, Causeway Bay) are at a standstill, but Central still functioning. Speculation that Xi Jinping is going to can CY Leung, try to buy off the student leaders with small gestures. A talk-first strategy worked well with both Tiananmen in 1989 and more recently with the Falunggong protests in Beijing. But once you have lulled protesters into a false sense of security in HK, it is not so easy to send in secret police to round up the organisers, let alone send in troops. This is a whole new ball game for the CPC…

Here are the early instructions from the Propaganda Dept to mainland media outlets about handling information on the Hong Kong protests, courtesy of China Digital Times:

<All websites must immediately clear away information about Hong Kong students violently assaulting the government and about “Occupy Central”. Promptly report any issues. Strictly manage interactive channels, and resolutely delete harmful information. This [directive] must be followed precisely. (September 28, 2014)

???????????????“??”????????????????????????????????????????????[Original text]>

At the end of this SCMP story on the protests is a 9-minute embedded video interview with student leader Joshua Wong (you will have to do some kind of registration to access this). It is well worth watching. Not only Beijing, but the HK tycoons, have a very serious young man on their hands.

Cordon created by police around Tamar/Admiralty, keeping protests out of central for now. 28 September