Air Portugal (TAP) may not be the absolute shittest airline on earth, but it tries hard.

On Monday last week I turned up at Heathrow for a flight to Abidjan in the Ivory Coast. The Gates’ and Rockefeller Foundations had very kindly bought me a Business Class ticket to go speak at the 2017 African Green Revolution Forum. I was sent the ticket details about a week earlier.

At check-in, however, the agent said that TAP had not completed the issue of the ticket because it wanted to do a ‘credit card check’. With which card had I paid?

I replied that like most people who travel in Business Class I had not bought my ticket myself. It was purchased for me by the travel secretariat of the AGRF, which I believed was based in Nairobi. If TAP wanted to do a credit card check, shouldn’t it have done one with the travel secretariat a week earlier when the ticket was ordered?

No answer. A phone call ensued between the check-in agent and the TAP office where someone was demanding this random check. I had thought there might have been a payment problem with the credit card, but the agent said this was not the case. TAP just wanted a random, at-the-airport credit card check with a Business Class passenger who had no idea which card had been used for the transaction.

After the call, the agent asked me if I was prepared to pay for the ticket on my card, since there was really no time to chase down the travel secretariat in Nairobi. Figuring that Gates and Rockefeller were good for the money, which was about £1,800, I said yes, because I didn’t want to miss the flight.

By now, however, 20 minutes had gone by and the computer system had automatically shut down the flight’s check-in. Increasingly frantic, the check-in agent started calling numbers of TAP back-office staff asking if they could take my payment over the phone and re-open the flight to allow my boarding pass to be issued. There were long discussions and calls to other numbers. At half an hour before take-off, I figured I was not travelling.

Just then, however, the senior TAP manager in the airport sauntered past. The check-in agent explained the situation. The manager picked up the phone, called the TAP office, and instructed them to issue to the ticket, charged to the original card. Then he told the check-in agent to walk me through security to the gate. We set off 26 minutes before take-off and arrived about 15 minutes before take-off.

It was all very weird. And it was only the beginning of TAP’s plans to fuck up my week.

The plane was 25 minutes late getting to Lisbon. It was a connection of only about one hour, and security in Lisbon seemed horribly slow and incompetent, at least by the standards of Heathrow or Stansted. A rather nervous woman from TAP who didn’t quite seem to know what she was doing was delegated to round up seven ex-London passengers and get them on the flight to Abidjan. Once we boarded the plane, having seen the chaos in Lisbon airport we asked the crew explicitly whether the check-in bags were on the flight. They assured several of us that they were.

Given that the airport is not huge, and the ground staff had about 50 minutes to make the transfer, there was no reason to believe the bags had not been loaded. Heathrow had loaded my bags in 26 minutes.

The flight was interesting. It was on a Airbus A320, which has a maximum range of about 6,100km (I make no claim to precise figures here; I am going by a quick online search). Lisbon to Abidjan is 6,000km. In other words, TAP was using a short-haul aircraft at the limit of its range.

The result was that, with a Business Class ticket, what one actually got was a Premium Economy seat. There was no greater seat width than an Economy passenger, just a bit more leg room and perhaps a few more inches of recline. The Irish gentleman next to me agreed that this is a business model that Michael O’Leary, CEO of Ryanair, would have a wet dream over.

Only two people served the Business section. They closed a curtain after take-off, and took what seemed to me the longest time I have ever experienced to get a meal ready. There was no drink for Business either before take-off, or immediately after. One person serving Business knew what she was doing; the other was clueless and appeared to be being trained on the job (another innovation for O’Leary). All these facets were exactly the same on the way back.

We arrived at Abidjan at about 1030pm. We watched as the baggage carousel rotated for about 90 minutes. No luggage appeared for the London passengers.

After five hours, TAP in Lisbon must have known that the baggage had not been loaded. TAP, as I later confirmed, has an office at Abidjan airport. But no one appeared to inform or help their luggage-less customers.

Instead, we had to register our missing bags (French language only, which was difficult for some passengers) with the general airport lost luggage office. We then took our chances with some pretty aggressive taxi drivers at about 1230am, arriving at the hotel just after 1am.

I arrived at the hotel with the following clothing resources: T-shirt bearing image of large pineapple; expensive jacket; brown corduroy trousers; sweaty boxer shorts; smelly socks; Danish boating shoes. I also had a green jumper in my backpack, but could not think how to make use of it in the tropics. Luckily, I knew the boss of one of the Lost Luggage Seven, and this person lent me a shirt for the start of the conference at 0745.

The conference, probably the key development event of the year for Africa, was full-on, but in the course of the day I managed to a) skip out to a French department store and buy pants, socks, trousers and a shirt for dinner with the vice president and b) track down a number and email address for the TAP office in Abidjan.

In the course of that day, no one from TAP attempted to contact the passengers.

A lady in the TAP office emailed eventually after I called her to say that they had located the luggage and it would not arrive until Wednesday, as there was no flight Tuesday. So would they bring it to the Sofitel, where we all were, I asked? No, she wrote, we would have to go to the airport and get it ourselves at 1030pm on Wednesday using our own transport.

I was the only person in the group who had managed to track down the TAP office, so at least I was able to tell three others whom I had contacts for what was going on. At no point, the whole week, did TAP contact anyone. Even though they could have done so via the original bookings, or via the email and phone numbers we left with the airport Lost Luggage office. They did not give a fuck.

I emailed TAP to ask if I would be compensated for the £150 I had spent on clothes and toiletries. The reply was vague, saying only that I should come to the TAP office. I checked Google Maps. It was half an hour away across town. I would not have time to go there before Friday, and then only if I was lucky.

On Wednesday we went to the airport, waited around for 90 minutes, and eventually got the bags. By a somewhat crafty manoeuvre I managed to recover not only my two bags but also that of the guy who lent me the shirt, who had essential work stuff to do that evening.

I had asked TAP if they would send someone from their office to assist us at the airport that evening and they indicated not. They were as good as their word. We saw no one from TAP all night.

At 4pm on Friday I got my first free hour of the working week and decided to go to the TAP office, if only to complete my anthropological and ethnographic research. The email about reimbursement said that I needed to bring my passport to the office, nothing else.

At the office, about 10 minutes in to a conversation with the woman who had been emailing me, she clarified that the most TAP were going to give me was US$100. In our correspondence, she had consistently refused to address whether I would be repaid the purchases of clothes for which I have no general use. Adding in the US$20 I was paying the hotel for a car that brought be to the TAP office, (because I couldn’t face doing this is an Abidjan taxi after working a 60-hour week), plus the Abidjan taxis that I had taken to do the clothes shopping earlier, I was now out US$200. Plus the AGRF had paid at least US$50 to provide a hotel car to take me to the airport to collect the luggage because it was so embarrassed by TAP’s behaviour (for which, of course, the AGRF has zero responsibility).

In order to get the US$100, the lady asked if I had the lost baggage receipt from the airport. Of course not, I said, because they take it from you when you get your bags back.

The lady said I should have taken a photograph of the receipt with my phone’s camera before handing it over. I agreed that I am an utter moron. However, since I had a copy of the TAP email correspondence with me, the lady had to concede that she had never stated that I should have or bring a copy of the lost luggage receipt.

The lady started to talk with her colleague, who assumed that I did not speak French. I don’t speak great French, but I had mainly chosen not to speak French in the TAP office because I wasn’t clear why I should do anything helpful to a firm that is so contemptuous of its customers. The woman who only spoke French appeared to be the senior person in the office. She made a call to someone apparently more senior than her. She noted that I was a Business Class passenger and referred to me as ‘impatient’.

I smiled. The French-speaking lady said to the English-speaking lady to get a photocopy of my passport. The photocopier was less than two metres from the French-speaking lady, but she did not make the copy herself. Instead, she called the office boy to make the photocopy.

At length, they gave me the US$100.

I had one last question: of the seven people from London whose bags were lost for two days, how many had come to the TAP office to claim US$100? The two ladies conceded that no other passengers had come.

Like me, other passengers would have had to find the TAP office by searching, get the correct phone number after discovering the one given online is wrong, work with a driver to locate the office (the address alone is not enough because the office is inside a small shopping arcade, while no directions are given online), and then found time during the working week to get to the office.

As I drove back to the hotel to get a beer after a very long week, I wanted to reach a reasoned conclusion about TAP, Air Portugal.

My conclusion was that the business is run by Mother. Fuckers.

Still, the key thing is that you can always find a positive. Check-in was a shambles; actually, it was worse. The Business Class seat was not a Business Class seat and hence a total rip-off. The service was slow and half the TAP employees did not know what they were doing. Lisbon airport security was pure Third World. Baggage handling was Third World. The loss of luggage for two days when they could have re-routed it faster if they wanted is off the spectrum for abuse of clients. And our treatment in Abidjan was frankly inhuman.

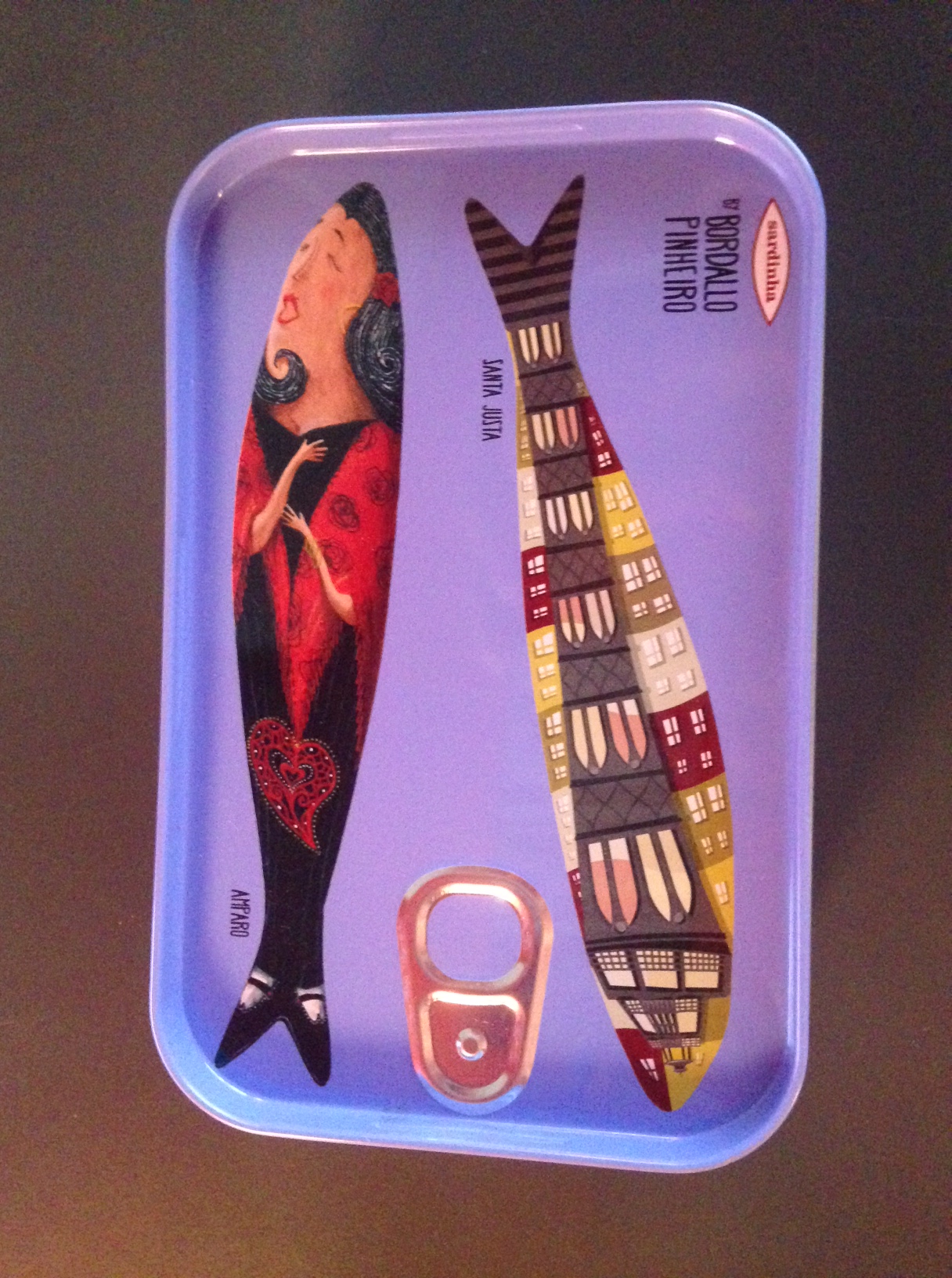

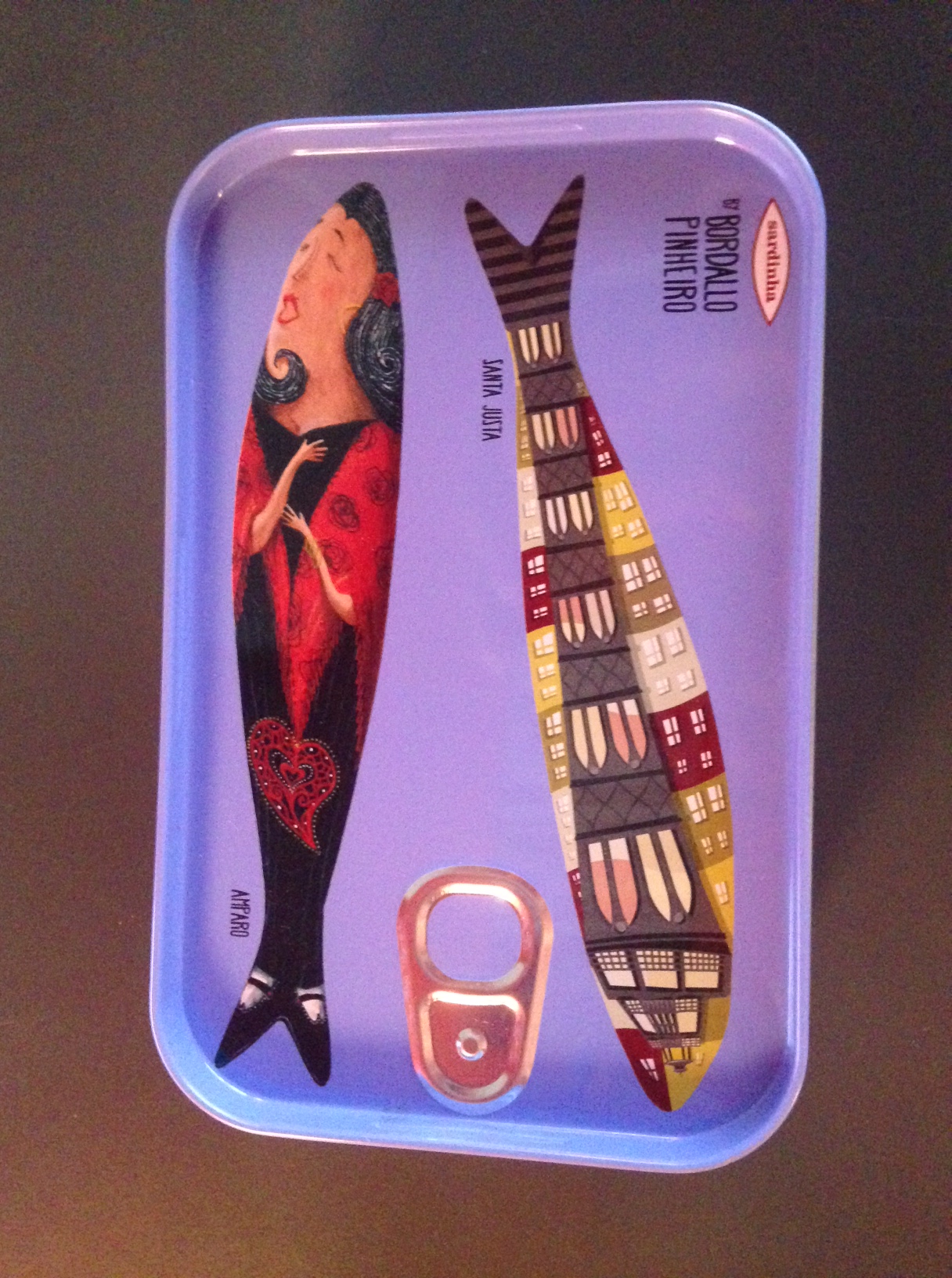

On the other hand, I did like the tin that the socks, ear plugs and eye mask came in. It is both original and recyclable.

More

In case you have never seen it, here is SNL’s Total Bastard Airlines sketch. I guess that European airlines, TAP (and Alitalia) excepted, are more civilised than American ones, so we have no European equivalent.

I will be saying Bub Aye to PAL. Perhaps you should too.

Email, Print, TwittyFace this post:

Like this:

Like Loading...