By Reuters

- Peter Thal Larsen

- What is the future for Africa’s economic development? Over the years, periods of high hopes for the continent’s prospects have swung to disappointment and back to hope again. Right now, it’s fair to say the mood has turned a bit gloomy again. Many African countries have been whacked by Donald Trump’s tariffs, which have upset their export markets. The United States, United Kingdom, and others have slashed aid budgets, and climate change is adding to the challenges facing many fragile African nations on top of the historic burdens of colonialism, slavery and the scourges of debt, disease and armed conflict which have blighted it in the past.

- Peter Thal Larsen

- The true picture is much more complicated than this. And there is a more positive story to tell, one where a handful of African countries have, with careful planning and thoughtful policies, transformed their economic prospects and where a population boom is creating the potential for future development and growth that have eluded most African nations in the past.

- Peter Thal Larsen

- So today on The Big View, we’re going to talk about African growth, the past, and more importantly, the future. It’s what we do at Reuters Breakingviews. We tap our best sources around the world for fresh insights into the biggest stories in business, finance, and economics. I’m your host, Peter Thal Larsen.

- Peter Thal Larsen

- Some people argue that it’s pointless to try and generalize about a continent which is home to 1.5 billion people spread across more than 50 nations spanning different history, geography, culture, and language. Others maintain that the conditions facing African countries are so historically and geographically unique that it is a mistake to try to compare their economic development to the experience of countries in Asia and South America. It’s fair to say my guest today disagrees. Joe Studwell is a journalist and academic who is currently a visiting senior fellow at the Overseas Development Institute. He’s spent much of his career living in and writing about Asia. But for the last five or six years, he’s been involved in an intensive and in-depth study of Africa. He’s written up his findings in a fascinating new book. It’s called “How Africa Works: Success and Failure on the World’s Last Developmental Frontier”.

- Peter Thal Larsen

- Joe Studwell, welcome to The Big View.

- Joe Studwell

- Hello Peter.

- Peter Thal Larsen

- So let’s start with perhaps the obvious question. I mean, you spent a big part of your career living in and writing about Asia. Your last book, admittedly some time ago, was called “How Asia Works”. You say in the introduction to this book, the project began by a mistake. What happened?

- Joe Studwell

- Well, there were two mistakes, really. One mistake was the Ethiopian and the Rwandan governments asking me to go and see them. And I said, well, I don’t know anything about Africa, so that would be pointless, even if it’s lovely of you to ask me. And they said, no, no, you don’t need to know anything about Africa. We want to talk to you about Asian development policy. And then the other one was a meeting with Bill Gates, who liked the last book. And with Gates I talked for an hour about Asia. But at the end of it, he said, “oh, you know, but what I’d really like to know is what you think about Africa”. And it was these events that got me thinking, you know, that perhaps there was something to be done. I knew it was going to be a huge project because there are 55 countries in Africa and it was going to take a lot of time. But Gates, the Gates Foundation, and Omidyar, which is one of the eBay founders, together said they were willing to fund the research. And that’s how it started and kicked off.

- Peter Thal Larsen

- And so you, you spent something like seven years, is that right?

- Joe Studwell

- I don’t think it was as much as seven years. It was five, six years in total. I wasn’t doing it the whole time, but I was doing it a lot of the time. You can imagine with stuff that you’ve covered in your career that you’ve got to get the historical backstory of different countries. You’ve got to recognize that there are different drivers of economic development in different places. It takes a long time, but I found it fabulous. I didn’t have a bad experience in Africa actually, and I met some really interesting, straightforward, get-ahead people. I thoroughly enjoyed doing the work.

- Peter Thal Larsen

- Because there is, I mean, there’s another potential challenge facing a book like this, which is how can you possibly generalize? As you say, there is more than 50 countries, different sizes, geographies, languages, political structures, colonial histories. So what made you confident that there was something that could be said that would be sort of relevant on a continent-wide scale?

- Joe Studwell

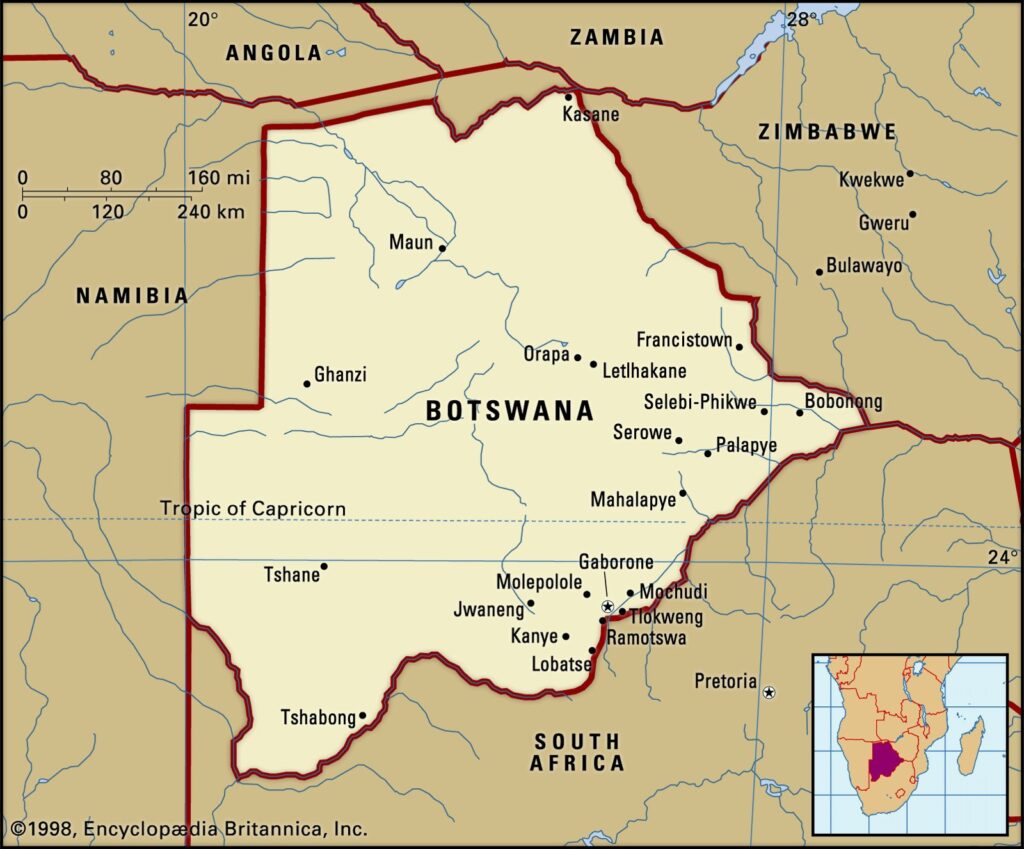

- I wasn’t confident — but I got into it and I thought, if there are themes, I’m going to find out what those themes are. And yeah, in the middle of the project, I thought I’m never going to find anything, any commonalities here, it’s just 55 different countries. But ultimately, as I pulled together more and more research, I began to see that no, and there is a pattern in Africa. And it’s a pattern that surrounds demographics, which was not something that I’d ever paid — it wasn’t that I hadn’t paid attention to it in Asia, but I hadn’t ever needed to be concerned because East Asia and South Asia always had sufficient demographic density for economic development, at least after the Second World War. You’d have to go back into the 19th century to find parts of East Asia, Southeast Asia, particularly, that were sort of problematic in terms of demographic density. But when I looked at Africa, what I realized was that that was the major constraint on the continent. We think about Africa today, people, I suppose, particularly in Europe and the US, are starting to get frightened by the population numbers that they’re beginning to get familiar with. So at the end of the Second World War, there were only 230 million people in Africa. Today, there’s 1.5 billion. In 2050, there will be 2.5 billion. At the end the century, there’ll be 4 billion people in Africa. So, you know, the standard reaction to this is the, is the Malthusian one that, oh my God, we’re going to sort of breed ourselves to extinction. But the developmental story, the real developmental story in Africa, is a different one. And it is that in 1960, at the time of independence, when some people were quite optimistic about African development, population density per square kilometer was under 10 people, fewer than 10 people per square kilometer. It’s not a lot. It’s about the same as historians reckon there were in Europe in 1500. And in 1500 in Europe, how much growth was there? Well, there wasn’t any growth. And the reason was there were not enough people. Today, we’re just getting in Africa to the population density that we had in Asia in 1960. The end of this decade we’ll be there. So even though it’s a couple of billion people at the end of this decade, in density terms, it’s only getting to where Asia was in 1960. And that is hugely important because without a minimum amount of demographic density, it’s really impossible to develop because you don’t have markets. You can’t afford infrastructure because when you work out the cost of infrastructure on a per capita basis, it’s just too expensive to build a road or a reservoir or whatever, per person. You don’t get the division of labor that you get with more people and you don’t get a bunch of other what economists call economies of agglomeration. So when all that stuff is missing, you’re really stuck. And that has been — and the core argument of the book is that has been — the biggest constraint on Africa to date, you know, the literature has tended to tell us that it’s been problems of governance, problems of corruption, kleptocracy, problems of ethnic conflict, problems of other civil strife. But those to my mind of mainly been proximate problems. The fundamental problem is that Africa hasn’t had enough people.

- Peter Thal Larsen

- That’s really fascinating. And I think, I mean, you even sort of, you make the point that, that this goes right back to even the sort of the pre-colonial period, and the colonial period, that actually the way in which the, the colonial countries administered their African colonies was with relatively little investment or kind of oversight?

- Joe Studwell

- Yeah, I mean, we tend to look back at colonialism in Africa and focus on the fact that it was quite brutal, but it’s more useful in understanding what happened in the colonial era to understand the finances of it. And the dearth of population meant that colonial governments couldn’t raise tax or they couldn’t raise sufficient tax to do anything very much apart from put very small numbers of people, of foreigners, of Europeans, in place, and then rule rural areas in Africa through either chiefs who existed already or chiefs who were put in place by the colonial powers. I mean, there’s research that’s looked at the colonial numbers were put in place in terms of expatriates that were put into place in British colonies in Africa. And each person, each colonial officer, which was usually a district officer, was looking after an area the size of Wales, which would be the size New Jersey in the United States. And so you can imagine. With a horse. You’re not going to get a lot done.

- Peter Thal Larsen

- Right — I suppose that’s probably right. So it’s clear, as you say, the demographic picture is changing very quickly now. Now you sort of present this as clearly as an opportunity in terms of this enables certain things. But it also, people also think about it as a risk. I mean, there’s a sort of Malthusian argument, but there’s also a sort of, I think the World Bank and others make this argument that you have lots of people who are reaching sort of working age in Africa and just, there are insufficient jobs to support them then — then what happens? I just wonder how you think about the balance of opportunities and risks?

- Joe Studwell

- I think obviously there are huge risks, but the point I make in the book is that you’ve got to have these people in order to be in the developmental game. Because if you don’t have sufficient density of people, at least, as I say, what we had in Asia in 1960, you’re not going to — you’re not going to get your economies moving. I came away from it preferring to feel optimistic, but I think you can look at the situation and be very pessimistic if that’s the kind of person that you are. I feel somewhat optimistic because the bit of the economy of Africa that you would expect to respond first to greater demographic density, which is agriculture, as was the case in Asia, is responding. So since 2000, we’ve had average agricultural growth, value added growth per year in Africa of about four and a half percent, all right. So that’s the fastest rate in the world. You wouldn’t expect most places in Asia to be faster now because they’re relatively mature in terms of their agriculture sectors. But nonetheless, it’s pretty impressive. And, you know, you can look around the continent, look at, you know, look at Nigeria, as one often has to because it’s the most populous country in Africa. Frequently described as chaotic, ungovernable. But since 2000, the data show that agriculture has been growing at nearly 6% a year, right? So that’s pretty impressive for a chaotic ungovernable country.

- Peter Thal Larsen

- You talked about how Ethiopia and Rwanda were interested in you talking to them about the Asian development, and you write quite a lot — Ethiopia and Rwanda are two of the examples that you explore in terms of where there’s been some lessons to be learned in part. I’m just wondering a bit about that comparison with Asia. Because what strikes me about the Asian development story, and what I took from your last book, “How Asia Works”, was really that they did things that were against the sort of the economic orthodoxy of the time, right? So that the countries that successfully developed in Asia, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, you know, they had tariffs, they had capital controls, you know, kind of, they didn’t open up their markets in the way that sort of that the consensus, the economic consensus would have suggested. What you’ve got here — but they didn’t really have, there wasn’t a template to follow. They were just sort of, they were just doing things differently. Whereas here it seems like there’s a more conscious effort to try and say, well, it worked in Asia, maybe it can work for us too. Is that fair?

- Joe Studwell

- I mean, that’s fair for Rwanda and Ethiopia, which have very, very definitely been trying to replicate Asian models. I mean Rwanda, very interesting, very focused on the Singaporean model, which sounds ridiculous, right? Because Singapore’s this little island on the main shipping lanes of Asia, and Rwanda is bang in the center of Africa. But actually, when you, when the Rwandans explain to you their logic, it does make some sense. Because they say, well, we are so remote and the cost of moving things here by truck is a multiple of what shipping from Asia or wherever costs, we can actually use our isolation to produce manufactured goods that wouldn’t be competitive in the world economy, but are competitive in the center of Africa. So them and the Ethiopians where, yeah, there’s just been a phenomenal appetite to absorb the lessons of development elsewhere, and people are fantastically well-read. Every other minister seems to have done a PhD on the side while being a minister, and the PhDs are all kind of looking at developmental problems. So they are like that. And other countries I would say are sort of less aggressively thinking that they’re going to replicate what’s happened in East Asia. But in a country like Nigeria, you’ll meet politicians like the current vice president who are very interested in learning lessons from East Asia, and then other countries, again, you don’t get a lot of direction to the sort of developmental thinking. But that isn’t quite the end of the world because what we see in Africa, and this is quite different to Asia where most development was state-led in some way or state-orchestrated in some way. What we see Africa and other African countries where there isn’t strong political leadership is we see the private sector leading. And most obviously at the moment, because of the growth, 25 years of accelerated growth in agriculture now, so we see private sector really being very active in the manufacturing bit of agriculture, which is basically making processed foods, everything from milling grain to actually producing packaged foods. And already we see a pattern where quite big companies are coming into being, working across eight, nine, ten countries, producing enough cash flow then to go into other businesses. So in Tanzania, one firm I talk about a little bit is Bakhresa. It’s the biggest agribusiness in Tanzania. It started in milling, bought mills in different countries when they were privatized by African governments. And now they’re in everything from petroleum products to real estate to a TV station, and I think they’ve got a football club as well. You know, so, and quite similar, I mean, Peter, I’m sure you’ll see the analogy or the comparison here, quite similar to those kind of Christmas tree businesses that grew up in Southeast Asia. So you think of CP Group in Thailand or the Salim Group in Indonesia or Astra in Indonesia —

- Peter Thal Larsen

- Big conglomerates doing lots of different things —

- Joe Studwell

- Yeah, but they all come out of agriculture. They all originally come out of agriculture, and then the cash is there, and they go and pursue a bunch of different opportunities.

- Peter Thal Larsen

- So this may be a good segue. I mean, you’ve talked about agriculture as being one of the key, the key sort of things to solve or is in the process of being solved perhaps. There’s manufacturing and obviously manufacturing was a huge part of the Asian development, for the successful Asian development. I guess the counterargument would be today that manufacturing has changed. Everybody’s adopting robotics and artificial intelligence. It’s a little bit the way people talk about India as well, is that the opportunity to do in Africa what was done in South Korea and Taiwan and other places that that moment has gone. How do you think about that argument?

- Joe Studwell

- I don’t think so. I mean, I think that technologically manufacturing is changing, but very slowly. But I think when you get very large, very low-cost labor supplies, that people remain very competitive against robots and AI. Manufacturing wage rates in Africa now are like $65 to $90 a month, compared to $600 or $700 in China. And then if you compare that with robots, if you look at garmenting, the sort of absolute lowest value added area of activity that countries first go into, a garmenting robot usually can’t do a huge amount of stuff because material, of its nature, is flexible. And robots like working with solid things. But I mean, it’s not going to cost you less than $100,000. And the problem with robots and putting robots into factories is you pay upfront the full amount. You know, you compare that with bringing labor in and laying labor off, which, in poor countries, you can always hire and fire labor as you want it. So a lot of manufacturers, that’s a lot more attractive at $65 a month than potentially overcapitalizing a manufacturing line. So I just don’t think that we are at the point where if you’ve got sufficiently affordable and reliable labor and political stability, that manufacturers are going to say, no, no, we’d rather work just with robotics. I think the more serious challenge to Africa’s ambitions in manufacturing is the competition that there will be from Southeast Asian states that still have a lot of low-cost labor, so Indonesia and South Asia. So is India going to bring a very large number of people into manufacturing? And if they do that with really good government support, then that I think can be more problematic for Africa. But still, at the end of the day, one thing that Africa has very much on its side is the logistics relationship with Europe. I mean, North Africa, totally so, right? I mean, Morocco, you’re 14 kilometers from Spain.

- Peter Thal Larsen

- You mentioned two important words there, political stability. Obviously, it’s very easy to say that there has been a history of particularly civil war in Africa. But also, I think one of the things that’s striking to me from reading your book is that actually, even against that backdrop, some countries have managed to do very well. You talk about Ethiopia, which obviously had the terrible famine that we all remember from the 1980s and then a period of growth, but also a really gruesome civil war in the 2020s. And yet the economy has continued to grow. And Rwanda came out of this terrible genocide and has had a lot of political upheaval and still managed to keep growing. I wonder how you rationalize that. From the outside, you would look at that and say those two things are inconsistent?

- Joe Studwell

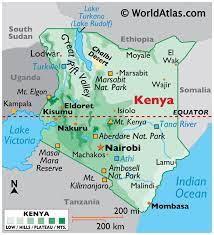

- Yeah. I mean, again, I think one can look at Africa today and be an optimist or a pessimist in terms of conflict that you see going on around the continent. To me, the main concentration of conflict and coups that we’ve seen in recent years has been the Sahel region, where you have a very particular story. It’s a very particular environment. It is very impacted by climate change, and so forth. And I don’t, so I don’t think that that is symptomatic of a political malaise more generally. But, you know, do you see conflict in other places? Yes, you do. I mean, we can’t deny that. And, you know, the ethnic diversity of the continent is at the root of this. And again, it goes back to demographics. I mean, historically, thousands of different ethnicities could survive in Africa because population was so low. And there was actually very little by European standards, very little conflict between different groups. And if you got in a disagreement and an argument, you could move off and find new land to inhabit. So ethnic strife is going to continue to be a problem. Ethnic conflict is going to continue to be a problem. I think though that one positive that I would point to, maybe not normally one that’s pointed to, is that if you look at protest in Africa over the last, say, five years, and you look at protests that we’ve all seen on the TV in Kenya, in DRC, in Mozambique, in Ethiopia. What’s quite striking to me, is that you see more and more evidence of protests being cross-ethnic. You see different ethnic groups. So it’s no longer about I’m this and you’re that. It’s about the issue. And I would actually point to that as potentially the front end of a positive trend in in Africa. But, you know, that said, unrest will continue to be a problem. We’ve just got to keep it in a bit of perspective. I mean, if you look at the number of people who’ve been killed in incidents in wars or domestic unrest with more than a thousand casualties since 1960, it’s reckoned to be around 6 million. Six million is the top end of the estimates of the number of people who died in Europe in the Napoleonic Wars, which were like a dozen years. So you’ve got to have a bit of perspective on this. It’s kind of too easy for us to look at Africa and say, oh, they’re violent people. I mean, anybody who knows the history of Europe would say we are extremely violent people.

- Peter Thal Larsen

- Yes, no, absolutely. Yeah. Well, and, you know, not that we, not that you want to get into a numbers game, but when you start looking at, you know, people who died in China during various great leaps forward and things like that, famines. One thing I’m just curious about, because I think there’s two things that probably feature less in your book than in most of the discussion about Africa that you hear or read at the moment, which was basically debt and China. There is this issue with a number of countries that are very heavily indebted, and trying to get out of their debt, complicated by the fact that they’ve also borrowed heavily from China. There was this whole argument that China’s sort of somehow trapped these countries into a sort of, into a debt dependency. I just wonder, I mean, obviously, again, it’s quite hard to generalize from country to country, but how do you think about that issue when it comes to Africa?

- Joe Studwell

- I mean, the first thing I think about is that African lending, to infrastructure projects and power projects in Africa, has brought capacity and resources that just would not be there otherwise. So if you add up what principally the Chinese policy banks have lent, but at other banks as well, it’s about $150 billion, okay. And that money was not going to come from anywhere else. So I would say that that’s been actually very important to African development, and Africa getting some basic infrastructure resources in place to begin to take advantage of its demographic growth. That said, has China overlent to some countries? And has it been opaque, in the extreme, in the agreement surrounding that lending? Yes, I think that’s certainly true. I mean, for instance, Angola, which is the biggest China debtor, we just don’t know. There’s a lot of speculation, but we just really don’t really know what exactly is in those loan agreements —

- Peter Thal Larsen

- Which is part of the problem —

- Joe Studwell

- Yeah, which is part of the problem. But I don’t see this as a Chinese conspiracy. I think that they really did, you know how they do everything as a campaign. I think they really did think that they were taking over the world and they were going to lend all this money to Africa and it was all going to get paid back. And they made some very poor decisions along the way. That has to be cleaned up. I mean, what I’d say from an African national perspective on this is that the number of countries in genuine debt distress is a small subset of all those in Africa. And one way or another, as with all debts, it’s going to have to be resolved.

- Peter Thal Larsen

- But you don’t see that as a — as a sort of a lasting impediment to development?

- Joe Studwell

- No, I don’t think so because I think most Chinese lending in Africa has paid for infrastructure and utilities that were needed. And in general, China has delivered those construction projects at a big discount in cost terms to what it would have cost to get the work done by European or US firms. And that’s what we tend to to forget, right? I mean, as with everything, China has cut half, or more, off the cost of doing infrastructure projects.

- Peter Thal Larsen

- We’re running out of time. I just sort of, just wanted to end on a, you know, as you said, you were sort of your — you chose to be an optimist about this. I thought there was, there’s an interesting sort of line at the end of the book where you say, “If you live outside Africa, whether in the Americas, Europe or Asia, Africa is going to be a bigger part of your life in trade, investment, tourism, literature, and music.” You sort of compare it almost to the impact that Asia was beginning to have in the 1960s and has had since then, which is quite an intriguing prospect. I mean, sort of, yeah, how would you sort of — how would you advise people to prepare for that?

- Joe Studwell

- I mean, there’s lots of interesting places to go and visit in Africa. People of our generation, if you want to see the deserted beaches that you saw in India or Southeast Asia in the 1980s, then you really need to go to Mozambique or Togo or another African country, because those are the only places that you’re going to see that. Yeah, it’s the last — it is the last frontier in that, in that respect. And, you know, it is also kind of a nice place to go if you’re coming from Europe, because there’s no jet lag, right? It’s all pretty much the same time zone.

- Peter Thal Larsen

- I see. Well, you’re doing — you’ve got a bright future as part of the African Tourist Board or something like that, if all else fails. But I won’t ask you which continent you’re going to write about next, but we can leave that for another time. But this was really fascinating, Joe. Thank you so much for taking the time.

- Joe Studwell

- Thank you for having me.

- Peter Thal Larsen

- That’s all we have time for this week. Thanks to Joe for that fascinating discussion. And as always, thanks to you for tuning in. This podcast was produced by Oliver Taslic, with the help of Mike Coupland and Jon Hodge in the studio in London. You can check out a new episode of The Big View every Tuesday. Don’t forget to tune into our sister show, Viewsroom, every Thursday, and all the other great podcasts from the Reuters team. To get in touch with feedback, questions and ideas, please email us on [email protected]. That’s [email protected]. If you like what you heard, please rate the show and leave us a review. And check out our views on the biggest stories in business and finance every day at Breakingviews.com and Reuters.com.