A series of notes from the world’s developmental frontier…

Botswana is one of only two exceptional African developmental success stories, in the sense of a state that transformed itself from poverty to upper middle income status – meaning from the fourth to the second of the World Bank’s income tiers — in only a generation following independence. (The other genuine success story is the tiny island nation of Mauritius.)

Botswana, in turn, offers two significant lessons for other developing countries, particularly African ones. The first is how Botswana was able to transform a traditional, localised, aristocratic ruling structure, led by tribal chiefs, into a modern, national, democratic political structure in which elite interests were sufficiently accommodated for them to accept the transformative process. The second is the results, positive and negative, that occurred when a poor but well-managed, resource-rich state followed strictly orthodox economic advice about how to employ its natural endowments to develop its economy.

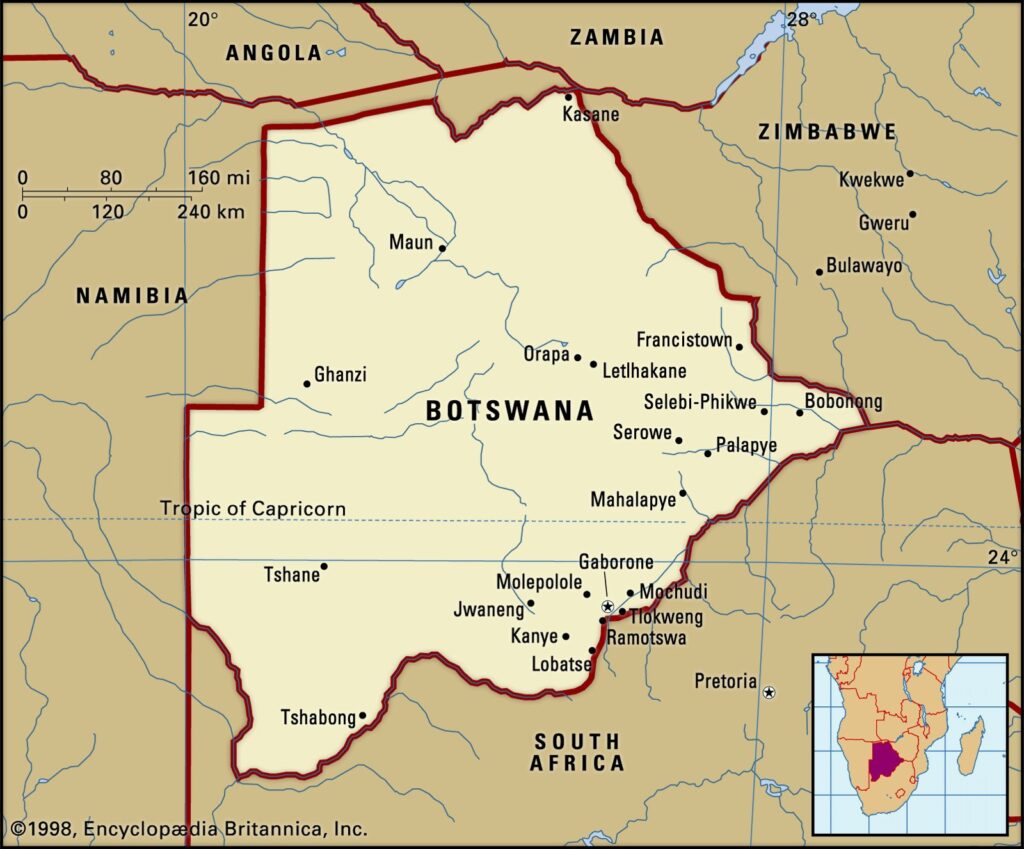

Botswana was defined in the colonial era by being a large, and largely desert-, territory surrounded by white minority-ruled settler states – South Africa, Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) and Namibia. As in Namibia, the main viable economic activity was cattle herding on semi-arid land. The heir to the throne of the largest ‘tribal’ grouping (the term the British used although majorities of each of eight designated ‘tribes’ were assimilated rather than descended from common ancestors) was Seretse Khama, who was exiled for more than five years because his marriage to a white British woman was deemed unbearably provocative to the apartheid South African government. Nonetheless, on his return in 1956 Khama worked closely with the last British Commissioner to begin to develop national institutions of government.

A Legislative Council was initially split half and half between African and European members, with Africans elected by a show of hands which ensured that cattle-owning aristocrats dominated the returns. When politicised Batswana – as the people of Botswana are known – miners working in South Africa formed a radical political party, Khama responded by forming an establishment party led by the African membership of the Legislative Council. The Botswana Democratic Party (BDP) went on to dominate Botswana’s politics until the present day.

Khama formed alliances with anyone committed to a national, if conservative, political programme. The most important was with Quett Masire, the son of a headman on the Bangwaketse Reserve, home to the second most populous group, who had been elected to the Legislative Council and went on to be Botswana’s Vice President, and later its second President. Masire was a highly successful agricultural entrepreneur. The British backed and trained Khama’s team, allowing it in the last years of colonial rule to operate like a full cabinet, to undertake policy formulation and to make grant pitches to the British Colonial Office.

Although Khama was a conservative aristocrat, he stood up firmly for the principle of racial equality. In 1962 he moved a motion in the Legislative Council to establish a select committee on racial discrimination. The report the committee published was the basis for ending the racial segregation that was unofficial but ubiquitous. Similarly, Khama saw off efforts by the tiny white minority in Botswana to retain the same political representation – meaning the same number of members of parliament — as the African majority.

Khama forced the political leaders of the white minority to come to terms with the reality of African majority rule and also convinced the chiefs of the eight ‘tribal’ groups to surrender key powers to a new national government. Under the terms of the post-independence constitution, the chiefs could not run for seats in the legislature but instead held unelected posts in an advisory House of Chiefs. ‘Advisory’ meant powerless. In addition, the constitution created District Councils, which took over the staff, offices, vehicles and most of the local government functions of the chiefs and former Tribal Councils. The chiefs were compensated with stipends and ex-officio seats on District Councils. By the time they understood the full extent of their loss of power, it was too late.

Khama, his government and the BDP were also careful to shore up their constituency of economic support. In 1963, a National Development Bank was established to provide credit to well-to-do cattle owners to sink boreholes in the western reaches of the Tribal Reserves, extending on to the sand veld of the Kalahari. In conjunction with big increases in state veterinary services and fencing construction from 1964-5 – the latter to limit the spread of outbreaks of foot and mouth disease – this built on a colonial strategy of subsidising large-scale cattle farmers. The BDP added the nationalisation of Botswana’s abattoir on the South African border, allowing for profit from meat sales to be returned to the big cattle owners who provided the abattoir with the vast majority of its animals. After independence, what became the Botswana Meat Commission (BMC) would also absorb losses onto the government’s account during downturns in the beef market, further subsidising big cattle interests.

The lower rungs of aspirational aristocrats and other entrepreneurs who sought bigger herds, credit and cattle-farming subsidies became the group which dominated among the BDP’s legislators and key supporters. When elections under the new constitution took place in March 1965, the BDP campaigned aggressively in rural areas – usually with the support of the local chief and dominant cattle interests — and won 28 of 31 seats in a new Legislative Assembly. Seretse Khama became Prime Minister and Botswana became independent in September 1966.

A reputation for reliability

Seretse Khama’s approach to politics was pragmatic and conservative, and his approach to economic development was very similar. Unlike the leaders of other newly independent states such as Zambia and Tanzania, Khama did not rush to localise the civil service, instead waiting until adequately-trained and experienced Batswana were available. By the mid-1970s, the number of Batswana civil servants tripled as part of a national training drive. However, the replacement of expatriates in the most senior civil service positions was only just beginning.

When the government lacked sufficient local teachers for its education programme, affordable imports were found in Ghana and India. Large numbers of American Peace Corps volunteers were recruited and given roles, in everything from teaching to the central government bureaucracy. A South African socialist and anti-apartheid campaigner, Patrick van Rensburg, was welcomed to open vocational training ‘brigades’ that enrolled thousands of young people. The approach to state capacity building was to pursue anything that worked.

The BDP leadership also made a point of leading by example. The key examples set were racial integration and frugality. Ministers made a point of joining new, racially-integrated sports and social clubs that were established in the capital, Gaborone. With respect to frugality, Seretse Khama was the only government minister to fly first class. Vice President Masire and other ministers travelled in economy.

The best resources in government were invested in a planning unit that was combined with the finance ministry to be a Ministry of Finance and Development Planning (MFDP). It was led by Quett Masire and set out economic development objectives in rolling five-year plans which were passed into law and could not therefore be changed without parliamentary approval. Under Masire, expatriate economists led by Oxford- and Harvard-trained South African Quill Hermans, and Cambridge-trained Briton Peter Landell-Mills, developed one of the best reputuations in Africa for reliable aid planning and for spending grant funds as promised. Already in the early 1970s, only Congo and Gabon received more aid per capita in Africa.

Botswana in 1966 had the commitment to collective action for national development, the pragmatic, ‘whatever works’ approach, and the nascent planning bureaucracy that characterised the most successful East Asian developmental states. When mineral discoveries were made by foreign companies in Botswana, the government was therefore equipped to manage their exploitation. The first deposits to interest multinational miners were copper-nickel ore around two remote settlements, Selebi and Phikwe, in the east. The second was a diamond-bearing kimberlite pipe at Orapa, in a more central part of Botswana, found by South Africa’s de Beers.

The copper-nickel project’s three linked mines, smelter, dam, rail spur, power station and town required investment equivalent to one-and-a-half times Botswana’s 1968-9 Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Masire and Hermans ensured that all investment risk, including debt guarantees, was held by the miners and financing agencies that supported them. Botswana secured a free 15 percent equity interest as the price of the mining licence, with royalties to be paid on operating profits in addition to corporate tax on profits and withholding tax on dividends. The Botswanan approach was vindicated when copper and nickel prices fell and the mine never made money. However, the mine did fund the build-out of Botswana’s power and water utilities, and road infrastructure.

It was the Orapa diamond mine, which opened in 1971, that changed Botswana’s future. In its first full year, 1972, Orapa produced 2.5m carats and accounted, via the government’s 15 percent share of profits, and taxes, for 10 percent of government revenues. De Beers requested to double its agreed rate of production and asked to commence mining two more diamond-bearing pipes at Letlhakane, 40 kilometres away.

The Botswanan planning team had followed the advice of independent consultants to stipulate that the original contract would be renegotiated in the event of ‘extraordinary’ developments. This clause was invoked and the government demanded the venture become a 50:50 joint venture, with De Beers still shouldering all investment costs. It took three years of negotiations, however the South African company eventually conceded even though, when taxes were considered, the new deal gave Botswana 65-70 percent of profits.

In 1976, the year after the new joint venture agreement was signed, De Beers announced the discovery of a kimberlite pipe in the south of Botswana at Jwaneng. Where Orapa yielded 80 carats per hundred tonnes of extracted material, and Letlhakane 30 carats, Jwaneng would yield 140 carats, leading it to become the most profitable diamond mine in the world. Once the three major sites were all functioning, from 1982, Botswana accounted for around a quarter of global diamond output and this share would rise further.

Botswana’s planning unit produced other important results with respect to the country’s foreign trade regime. Following independence, Peter Landell-Mills set out to renegotiate the terms of Botswana’s membership of the Southern Africa Customs Union (SACU), which had not been reviewed since 1910. The planning unit secured a deal for Botswana based on current customs receipts plus a multiplier of 1.42 to compensate for having a tariff regime set by South Africa. The effect was to immediately increase customs revenues from Rand1.4m in 1968, the last year of the old formula, to Rand5.14m in 1969. When mine development began in the 1970s, requiring imports of large amounts of dutiable equipment and accelerating economic growth that in turn encouraged further imports – customs receipts rose much further, helping Botswana to balance its current budget from 1972.

In 1976, Quill Hermans led the launch of a domestic Botswanan currency, the Pula. Previously, Botswana used the South African Rand, however the MFDP wanted a domestic currency so that foreign exchange reserves generated by mining exports were managed by a new central Bank of Botswana. A national currency, with locally-managed controls on movements of capital, also allowed Botswana to limit the appreciation of the Pula during the mining boom and thereby protect the interests of cattle exporters.

In the first two decades after independence, Botswana’s economy grew at more than 13 percent a year as mining came to account for half of GDP. The share of mining receipts in government income rose even faster, to a quarter of revenues in the mid-1970s, and more than half in the mid-1980s. At the same time, Botswana’s reputation for planning and project delivery maintained high levels of foreign aid. In the second half of the 1970s, aid still constituted one quarter of Botswana’s total government expenditures. From being one of the poorest countries in the world, the question for Botswana became how to employ surpluses.

Absence of policy vision

In deploying surpluses, however, what Botswana lacked was any vision for structural change that would better fit its economy to the needs of its people. There was no vision for the large numbers of small-scale farmers and cattle herders in rural areas and no vision for manufacturing and industrial development to provide jobs for semi-skilled city dwellers. Like the national leader, Seretse Khama, the administration was fundamentally reactive, dealing with opportunities and challenges effectively, but with no overarching, proactive strategy beyond the long-established support for big cattle. The role of orthodox economists – who were not a feature of the early developmental states of East Asia – encouraged this; they looked to make the current state of affairs as efficient as possible, not to structurally re-shape the economy. With the benefit of hindsight, Festus Mogae, Botswana’s third President, concludes: ‘We reacted to situations as they arose but failed to imagine our future.’

MFDP economists concentrated investment in education, healthcare and basic infrastructure. Secondary school enrolment, for instance, increased from 1,531 pupils in 1966 to almost 10,000 a decade later. Hospitals increased from seven in the early 1970s to 30 in the 1990s and life expectancy rose from 48 years in 1966 to 65 in 1990. Paved roads increased from 12 kilometres in 1966 to more than 8,000 kilometres by the end of the century.

These investments, however, were not enough to prevent large swathes of the rural population living in poverty. There was a continuation of the private borehole drilling that effectively privatised communal land to large herd owners who could afford the wells. In Botswana’s Central District – what had been the Bamangwato Reserve and the biggest concentration of cattle grazing – fewer than 500 individuals gained de facto private grazing rights over a quarter of the area.

An inclusive agriculture policy would have prioritised small-scale cattle farming and involved local communities in managing communal land. However, such a strategy was never considered. In the 1990s, an estimated five percent of the population owned half the national herd. It was a large-scale but low-efficiency cattle economy and was accompanied by a steady increase in the proportion of rural families reporting they owned no cattle — from 28 percent in 1980 to 46 percent in 1999.

Such families formed the core of the rural poor – a large block making up about one quarter of Botswana’s working population. From the 1970s, as diamond revenues increased, the government’s policy to address rural poverty was to increase subsidies to arable agriculture. However, rainfed arable agriculture in almost all parts of Botswana is so precarious that it only works as a counterpart to less rain-dependent cattle ownership. The subsidies are in effect disguised welfare transfers.

Apart from small-scale farming, the other sector in which the Botswanan government could help to create employment opportunities for a population with limited education was manufacturing. The mines which produced so much profit employed only ten thousand people and new entrants to the labour force in the 1970s were twenty thousand a year. However, manufacturing policy was incoherent. This reflected the dominance of orthodox economists in government who knew that a mineral-driven economy needed to diversify but who were ideologically sceptical of the use of subsidies to induce manufacturing expansion. A lack of conviction led to dabbling in state-led import substitution projects on the one hand, and an unwillingness to aggressively subsidise private sector exporters on the other.

The Botswana Development Corporation (BDC) was created in 1970 as the country’s vehicle to invest in industrial projects. However, it limited its activities to the most basic, low value-added import substitution, including a brewery, a soap factory and a flour mill. There were no investments in more complex industrial plants, such as cement or large-scale metal working. Over time the BDC put more and more of its investment into real estate projects. The government was unwilling to subsidise credit and electricity prices for export-oriented manufacturers – the types of intervention that underwrote export manufacturing expansion in east Asia.

Instead of subsidising manufacturing at scale with firms’ competitiveness tested by their capacity to export – the crux of the East Asian model — from 1982 Botswana implemented a programme to provide subsidies to enterprises based on their employment generation. The Financial Assistance Policy (FAP) provided up to 90 percent of the capital cost of starting a business, and 80 percent of wages, declining to 20 percent, over five years. The programme ballooned, and was characterised by increasing abuse, over 20 years. The manufacturing share of the economy remained stuck at 4-5 percent as FAP projects closed down when grants ended.

The one area in which government did eventually deliver a little manufacturing success was the cutting and polishing of diamonds, which it was able to orchestrate as part of its periodic renegotiations with De Beers. In a deal signed in 2011, De Beers was compelled to relocate its global wholesale diamond aggregation and trading operation, which sells to its approved ‘sightholders’, or wholesale buyers, from London to Gaborone. As of 2018, eight sightholder cutting and polishing operations were running and total downstream diamond employment was around 3,000 people.

Overall, however, the orthodox economic prescription in Botswana left elevated levels of poverty and inequality despite rapid and sustained economic growth. The sectoral economic focuses of East Asian developmental states such as Japan, China or Vietnam on smallholder agriculture and manufacturing, which brought very broad-based development, were absent. Instead, in a Botswana whose population today is 2.3 million, there are only 340,000 formal jobs. Of these, the private sector accounts for 190,000, of which manufacturing is less than 40,000. The other 150,000 public sector jobs are in central and local government. Four times as many people work for the government as in manufacturing.

The failure to create more private sector jobs leaves large numbers of Batswana dependent on welfare of one form or another — 60,000 employed on a work-for-welfare scheme, 70,000 destitutes and orphan carers who exist on welfare, and 150,000 subsistence farmers who survive through subsidy programmes. Ellen Hillbom, a Swedish academic specialised in Botswana’s development, emphasises the contrast between Botswana and the developmental states of East Asia by describing the former as a ‘gatekeeping state’. The BDP gatekeeper, she argues, delivered a stable coalition based around a cattle-owning elite that managed mineral wealth in a disciplined fashion. However, Hillbom says: ‘Stability has lacked original thinking about how to change society.’