I have mixed emotions about Fat Pang, or Chris Patten, the last governor of Hong Kong. I guess I am just suspicious of British Tory politicians holding forth about matters of political principle in former British colonies. When Fat Pang was recently arrived as governor, I asked to interview him about his understanding of British colonial history (he read history as an undergraduate). His press manager asked what books I had read on the subject, and for a rough idea of questions. When I provided the requested information, the interview failed to materialise.

Nonetheless, Fat Pang’s Man of the Year article from Project Syndicate (original version and subscription details here), is worth a read. It is, of course, about the estimable Jimmy Lai.

…

Dec 17, 2020 Chris Patten

By jailing fearless Hong Kong pro-democracy campaigner Jimmy Lai on charges of breaking its new national security law, the Communist Party of China intends to reinforce the new limits to the rule of law, dissent, and autonomy in the city. But imprisonment often ennobles fighters for democracy and bolsters support for their cause.

LONDON – On December 12, Jimmy Lai, a successful businessman and brave campaigner for freedom and democracy, was led into court in Hong Kong in handcuffs and chains, accused of breaking the national security law recently imposed by the Communist Party of China (CPC). The Chinese authorities’ goal in charging Lai was to reinforce the new limits to the rule of law, dissent, and autonomy in the city.

The judge was handpicked by Hong Kong’s pliant chief executive, Carrie Lam, whose primary responsibility is to execute the CPC’s malevolent instructions regarding the city. Supporters of the 72-year-old Lai, including Catholic Cardinal Joseph Zen, were in the courtroom to witness him being denied bail until a trial scheduled for April 2021.

The Chinese government hates Lai, because he embodies a passionate belief in freedom, and we must hope that any time Lai spends in prison will be in Hong Kong rather than the mainland. His handcuffs and chains are a tragic symbol of what has happened to Hong Kong’s once-free society in 2020.

The CPC has of course victimized us all this year. The party initially covered up the COVID-19 outbreak in China and silenced brave doctors when they tried to warn the world about what we would soon face.

Some national leaders have added to the gloom. US President Donald Trump’s refusal to accept the result of an election that he lost by seven million votes has undermined America’s democratic system. His appalling behavior – abetted by Republican leaders and the GOP’s media allies – demeans him and his party and weakens the case for liberal democracy everywhere.

Meanwhile, Russian President Vladimir Putin continues to connive in the security services’ murders of his opponents and to undermine democratic states wherever he can. Other authoritarian leaders, from Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdo?an to Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, have consolidated illiberal regimes by changing their countries’ constitutions and electoral systems.

But it is Chinese President Xi Jinping who has represented the most serious threat to liberal democratic values this year. Exploiting the world’s preoccupation with the pandemic, Chinese forces have killed Indian soldiers in the Himalayas, sunk and threatened other countries’ fishing vessels in international waters, and menaced Taiwan. Xi’s regime has also continued to pursue genocidal policies toward Muslim Uighurs in Xinjiang, in addition to targeting Hong Kong’s freedoms.

When Hong Kong returned from British to Chinese sovereignty in 1997, China’s leaders promised in an international treaty lodged at the United Nations that the city would continue to enjoy its way of life and high level of autonomy for 50 years. That promise, like so many of the CPC’s undertakings, has now been junked.

China was clearly horrified that elections and demonstrations increasingly showed that the majority of people in Hong Kong refused (like the Taiwanese) to accept that to love China, they had to love the CPC. But at least two-thirds of Hong Kong citizens were themselves refugees or relatives of refugees from the horrors of China’s communist history.

These people wanted to retain the system that had helped them prosper and made Hong Kong an international economic hub. The city’s governance, like that of other free societies, was based on the separation of executive, legislative, and judicial powers, freedom of expression, and a market economy.

These aspects of an open society terrify Xi’s regime. The CPC’s control depends on party bosses at the center maintaining an iron grip on everything. Universities and schools must be “engineers of the soul,” to use Stalin’s phrase. Courts should do what the CPC tells them. The free flow of information is too dangerous, and any notion of democratic accountability must be stifled.

Countries from Australia to Canada that criticize some of the CPC’s behavior are singled out for commercial bullying, or worse. China has taken two Canadian citizens hostage because of Canada’s 2018 decision to detain a senior executive of Chinese telecommunications firm Huawei; the men are about to spend a third Christmas in solitary confinement.

This year, it was Hong Kong’s turn. The comprehensive stifling of the city’s freedom has proceeded remorselessly, encompassing schools and universities, the legislature, courts, civil service, and the media. All dissent is to be crushed, with democracy campaigners thrown into prison.

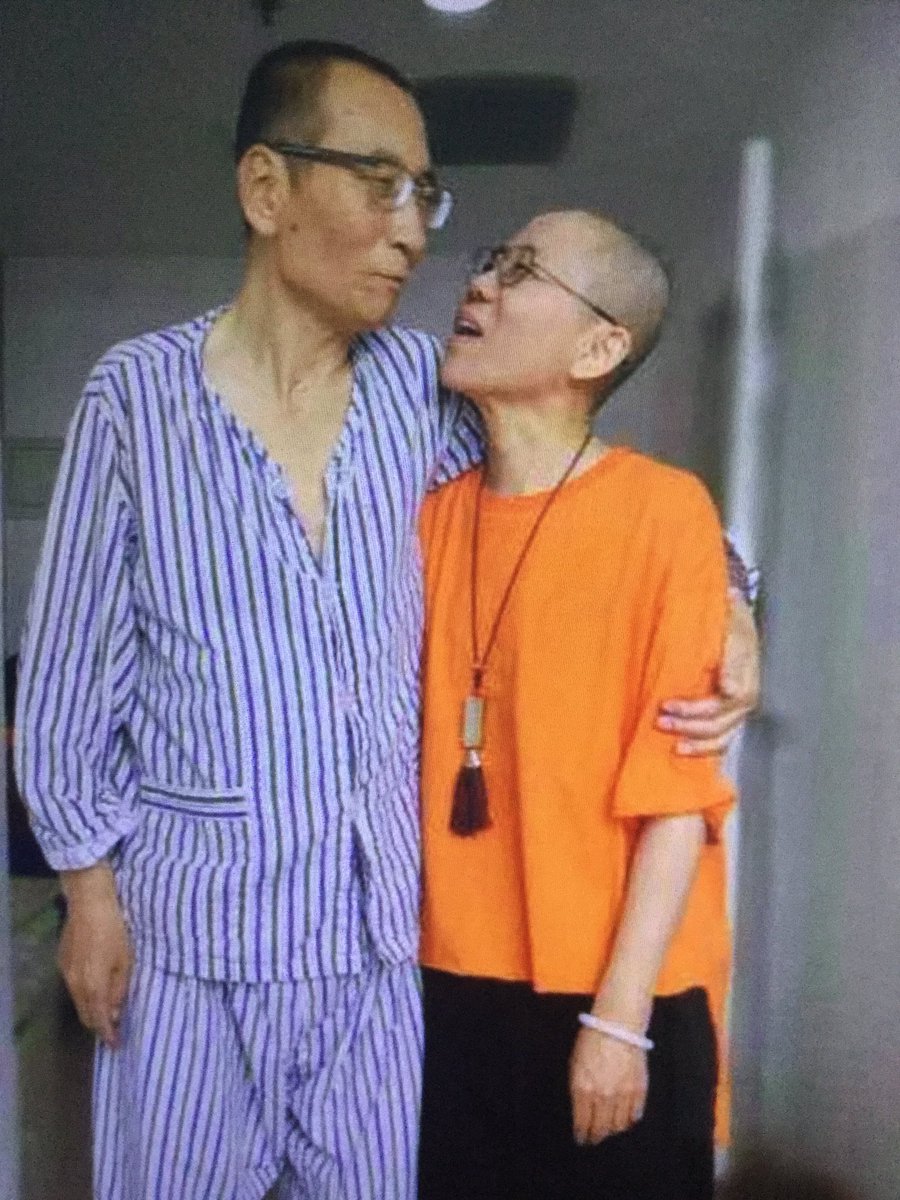

Lai is the latest and most prominent victim of the CPC’s idea of law, which the American China scholar Perry Link once described as like “an anaconda in the chandelier.” Lai was born in China but escaped to Hong Kong as a 12-year-old stowaway without a penny to his name. He worked in a garment factory, earned enough to start his own business, and founded the international retail fashion chain Giordano.

Lai never forgot that it was freedom and the rule of law that allowed him and others to prosper, and he denounced communism’s contempt for both. After the 1989 massacre of demonstrators in Tiananmen Square and elsewhere in China, he criticized then-Chinese premier Li Peng directly. As a result, his home and businesses were attacked and bombed by United Front communist activists and their fellow travelers in Hong Kong’s criminal triads.

Forced to close his garment business, Lai established a hugely popular magazine and newspaper group. He strongly supported democracy and never toned down his criticisms of Chinese communism. A devout Catholic, Lai regarded Hong Kong as his home, and was determined to stay and fight for the city he loved.

For the apparent crimes of principle and courage, and his refusal to surrender his beliefs, Lai has been targeted by a vengeful CPC with the collaboration of a few Hong Kong lickspittles whose reputations will forever be tarred by shame and infamy. But imprisonment often ennobles fighters for democracy and bolsters support for their cause: think of Martin Luther King, Jr., Nelson Mandela, or Václav Havel. And now think of Jimmy Lai, my man of the year.