A series of notes from the world’s developmental frontier…

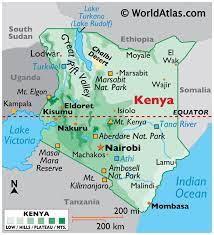

In logistical terms, Kenya is the most important country in East Africa. British colonial investment in the port of Mombasa and the rail line – dubbed the ‘lunatic line’ because of its cost and ambition — from Mombasa to Kisumu on Lake Victoria, and later to Kampala, means Kenya has long dominated trade access to Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi and the eastern portion of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Mombasa also handles a portion of Tanzania’s international trade. This logistical significance, the possibility that Kenya could become a manufacturing centre for the region, and the existence of fertile land along the coast, in the Western Highlands to the north-west of Nairobi, and around Lake Victoria, have long engendered optimism about development prospects.

From independence in 1963 to 1980, Kenyan growth averaged an impressive 7.1 percent. However, the start of a series of fiscal crises and World Bank and International Monetary Fund structural adjustment programmes in 1980 saw average growth fall to 2.9 percent from 1980 to 2003. Since 2004, growth rebounded to an annual average 5.4 percent. In each of these periods, Kenya was comfortably ahead of the overall sub-Saharan growth rate. With nominal GDP per capita of US$2,075 in 2020, Kenyans are the most prosperous citizens among major East African economies. The poverty rate, on the World Bank’s US1.90-per-day measure, fell from 44 percent in 2005 to 37 percent in 2016. Ostensibly the most impressive feat in the long run has been educational gains. In 1967, Kenyans had an average of just 1.7 years of education; today the figure is 10.7 years. Unfortunately, testing suggests that much of the education is of low quality; according to the World Bank, 60 per cent of 19-20 year olds who have been through secondary education still fail to meet basic literacy standards.

Déjà vu colonialism all over again

What stands out most in Kenya is how little government imposed itself on the economic structure inherited from the colonial era. In agriculture, there was a significant redistribution of white settler-owned land. However, this was a response to the insurgency by landless black farmers that started in 1952 – known popularly as the Mau Mau rebellion – which drew a policy response during the colonial era. From 1954, the Swynnerton Plan supported ‘loyalist’ and generally well-to-do indigenous farmers to move into cash crops like coffee, from which they were previously barred, on consolidated and privately-owned landholdings. From 1962, on the eve of independence, the British government funded the Million Acre Settlement Scheme which purchased white settler farms and again generally favoured better-off black farmers, with typically less fertile areas allocated for ‘high-density’ settlement by poorer and landless farmers. The post-independence government of Jomo Kenyatta went along with this approach, with Kenyatta famously dismissing landless Mau Mau rebels as ‘hooligans’. This was despite strong research evidence in the late 1960s that the poorer farmers with smaller holdings, who were also given much less agricultural extension support than better-off farmers, performed better.[i]

After Kenyatta defeated and ousted a minority of progressive politicians in the late 1960s, Kenyan agricultural policy showed striking continuity with the colonial era. The major difference was that the elite of large-scale landowners was now black. The Kenyatta family itself became, and remains, one of the biggest landowners, including a vast tract of thousands of hectares that extends north-east of Nairobi towards Thika and other large farms in what were known as the White Highlands – the region scheduled by the British as a white-only farming area. The redistribution of land to a black elite, limited redistribution to ordinary Kenyans, and the growth of black cash-crop farming was enough to stabilise the rural situation after independence. Tea did particularly well and continues to account for one quarter of Kenya’s export earnings. However, government agricultural policy has been remarkably passive. The great bulk of agricultural exports, including tea, continue to be unprocessed in the absence of investment to add value locally. Only 13 percent of land with the potential for irrigation has been developed and farming remains 98 percent rain fed. And where members of the African Union have been committed for almost 20 years to spending one-tenth of their budgets on agriculture, Kenya’s leading rural research institute, Tegemeo, puts the Kenyan share – including national and local funds – at around five percent. In the past two decades, the estimated contribution of agriculture to overall growth has been higher in Ethiopia, Rwanda and Tanzania than in Kenya.

When significant developments do occur in agricultural markets, they tend – as with so much in Kenya – to be driven by elite political interests or those of particular ethnic voting blocks. Jomo Kenyatta’s successor, Daniel arap Moi, built up the National Cereals and Produce Board, which bought up surplus maize, often at above-market prices. The vast majority of the maize surplus in Kenya comes from Moi’s ethnic Kalenjin base area in the Rift Valley.[ii] Under current president Uhuru Kenyatta, a son of Jomo, the Kenyatta family business Brookside Dairy became Kenya’s dominant milk processor, buying up competitors and acquiring a market share around 45 percent. In 2020, the Kenyan government banned the importation of cheap Ugandan milk, apparently in breach of East African Community (EAC) trade agreements. According to Kenyan economist David Ndii, under the Kenyatta government since 2013, milk processing margins quadrupled, the cost of processed milk to the consumer doubled and the price paid to farmers, at its nadir, halved, although it since increased following protests.

Plans that were not. And now China

Policy plans are sometimes announced in Kenya, but they have never proven to have implemented substance. After the fall of the Moi regime, a much-heralded Strategy for Revitalising Agriculture was announced in 2004. It delivered little before being abandoned in 2010. A grand plan of the current president promised to increase the share of manufacturing in gross domestic product (GDP) to 15 or 20 percent by 2022, with 500,000 or one million new manufacturing jobs created. Different targets appear on different pages of the presidential web site, perhaps an indication of the lack of seriousness the promise.[iii] In the event, according to World Bank data, the manufacturing share of Kenya’s GDP fell from 10.7 percent in 2013, Uhuru Kenyatta’s first year of office, to 7.5 percent in 2019, a record low in the independence era. One, real-world indicator of the state of industrial policy in Kenya is a sprawling, 2,000 hectare dustbowl with a few small buildings 60 kilometres south of Nairobi. This is ‘Konza Technopolis’, a high-tech production centre and suburb announced in 2008, with a master plan approved in 2013. Today, the only real evidence of progress at Konza is a web site with various digital images of what was hoped for.[iv]

The Kenyan government’s inability to deliver on its economic policy agendas may have contributed to its interest in infrastructure projects outsourced to Chinese firms. A journey along the country’s logistical spine, from Mombasa via Nairobi to Eldoret, reveals a large number of Chinese road projects currently under way. Around Mombasa, there are several operational sites including the Dongo Kundu southern bypass with four bridges that will connect the route south to Tanzania to the main Nairobi road. On the south side of Nairobi, the first phase of a planned expressway to Mombasa, currently contracted as far as Machakos 40 km from Nairobi, is under construction. Within the city, there are several other projects. In the north-west of the capital, along Waiyaki Way, the 27km Nairobi Expressway, some of which is elevated, will connect the north-west of the city to the international airport in the east; construction is at full throttle. A second route north-west out of Nairobi via Ruaka and Ndenderu has a Chinese financed and constructed road in progress. Around Nairobi, there are several more ongoing Chinese road construction projects.

Three hundred kilometres north of Mombasa, at Manda Bay near Lamu, the Kenyan government engaged China Communication Construction Company (CCCC) in a US$480m contract to build the first three of 32 planned berths at a new port it claims opened a first berth in May. The facility, in a remote part of the country, is part of the grandiose Lamu Port-South Sudan-Ethiopia Transport Corridor (LAPSSET), designed to link the economies of three countries to Lamu, which requires large additional investments in road networks. In April 2021, the government in Nairobi announced it has signed with CCCC for 453km of highway construction, including a 257km link north-west from Lamu to Garissa, at a cost of US$166m.

Much the biggest, and most controversial, Chinese project is Kenya’s new Standard Gauge Railway (SGR). The link from Mombasa to Nairobi cost a reported US$3.6bn and an extension to Naivasha, 110km north-west of Nairobi, a further US$1.5bn. The logic of the investment was to reduce freight costs, and accelerate freight times, all along the key logistical route through Kenya to Uganda and the rest of central Africa. However, this does not seem, so far, to have happened. While shipping costs per container on the Mombasa to Nairobi section, which opened to freight in 2018, are similar to road haulage, the addition of depot charges and the cost of moving containers from the railway to final destinations increased costs by up to 50 percent. China’s Exim Bank terms for the loans for the line required guarantees of minimum container volumes which in turn led the Kenyan government to compel all inbound containers destined for the Nairobi region to use the rail service. Despite this, the line has posted substantial losses – US$200m (KSh21.7bn) from inception to May 2020 according to the Ministry of Transport. In 2019, China decided not to provide the further US$4.9bn loans required to complete the connection to Uganda.

It remains unclear what the outcome of the rail project will be. At Naivasha, an Inland Container Depot has been constructed for container transfer to trucks, but is not yet operational. At the same time, a 24km link line is being built by Chinese contractors to connect the SGR to the old, colonial metre-gauge railway (MGR), which Chinese firms have been contracted, along with the Kenyan military, to refurbish. At one site in Eldoret in March, a small team of Chinese was overseeing the reshaping of colonial-era railway sleepers with an imported stamping machine. The Ugandan government announced in 2021 that it will also refurbish its stretch of the historic MGR. What this means for freight costs, however, is impossible to say. Containers will have to be moved between rail bogies on different gauge tracks. The temptation for the Kenyan government to force containers to use the two-gauge route in order to recoup its vast investment may be difficult to resist, leading to monopoly pricing. But if freight costs do not fall across Kenya and into central Africa, the economic logic of the rail project is defeated. Kenya already runs a trade deficit of around six percent of GDP, and higher freight costs will only increase the export shortfall. The World Bank’s 2013 report that said the SGR did not make economic sense appears to be vindicated.[v]

Debts up, revenues down

According to the China Africa Research Initiative (CARI) of Johns Hopkins university, Kenya is one of the top five African countries contributing to revenues of Chinese engineering and construction companies, along with Algeria, Nigeria, Egypt and Angola. CARI identified 43 Chinese loans to Kenya, totalling US$9.2bn, by the end of 2020; at US$6.1bn, loans for transportation projects are second only to Angola. From the Kenyan perspective, the Chinese projects saw public debt as a share of GDP rise from 39 percent in 2013 to 66 percent in 2020, with an increasing share from more expensive commercial sources. According to David Ndii, half of debt is now domestic, at rates of interest over 10 percent, accounting for three-quarters of interest payments. Meanwhile, government revenue as a portion of GDP fell from 18.1 percent in 2013-14 to 16.1 percent in 2018-19. The IMF this year described Kenya as ‘at high risk of debt distress’.[vi]

The situation places great weight on Kenya’s vaunted private sector to carry the economy forward. Entrepreneurial innovation in Kenya is certainly impressive. M-Pesa (meaning ‘mobile money’), the mobile phone-based payments and lending service developed by Kenya’s Safaricom, has come to be used by more than 70 percent of the population, and expanded regionally. Kenya produces significant numbers of agile, private-sector start-ups every year. Peter Njonjo, a former Africa executive with Coca Cola, started Twiga Foods in 2014, which provides the logistics to link farmers with small-scale retailers. Unable to overcome the product quality problems of smallholder farmers in an environment of weak government support, Twiga is integrating larger-scale commercial farms in the region into its city-focused distribution network. It is a typical case of the Kenyan private sector adjusting to what is possible and Twiga has won investment from the World Bank’s private sector lending arm and Goldman Sachs. ‘The lack of government involvement has led the ecosystem to evolve in a very informal way,’ says Njonjo. The private sector’s job, he says, is to find a way through this.

Kenya should be a processing hub for farm products. Led by private sector firms, regional trade in foodstuffs is already much expanded. In March, for instance, potatoes on sale in Kenya are likely to be from Tanzania, plantains from Uganda, reflecting relatively stronger growth of regional trade in East Africa compared with West Africa. Nonetheless, the space available to the private sector in Kenya is less than the government’s rhetoric suggests. There are still more than 300 state sector firms operating in the country despite decades of World Bank and IMF-led ‘reform’ programmes — in retail, manufacturing and agri-processing sectors among others. At the same time, as a recent World Bank report observes: ‘Prominent government officials often have large private sector interests and influence public procurement and government priorities through the use of proxy companies.’[vii]

As noted, Kenya has run ahead of the average sub-Saharan growth rate for several decades. To recognise more of its potential, however, the country needs more competition and more export-focused private sector activity. However, it is difficult in the current political climate — dominated by a small number of what Kenyans term ‘royal families’ that consistently failed to frame an economic development agenda — to see this happening. Kenya, for instance, opened Export Processing Zones in the 1990s at the same time as Bangladesh; but policy implementation failings mean that today Kenyan EPZs employ around 50,000 workers versus four million in Bangladesh. The more likely trajectory for Kenya is towards another debt crisis and a new round of World Bank and IMF interventions. Before that, there will be the next Kenyan election, in 2022, and the possibility of renewed ethnic violence on which Kenyan politics all too often feeds.

[i] Leo, C. (1978). The Failure of the ‘Progressive Farmer’ in Kenya’s Million-Acre Settlement Scheme. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 16(4), 619-638.

[ii] Poulton, C. and Kanyinga, K., 2014. The politics of revitalising agriculture in Kenya. Development Policy Review, 32(s2), pp.s151-s172.

[iii] See https://www.president.go.ke/enhancing-manufacturing/ and https://big4.delivery.go.ke/ The manufacturing targets were one element of an agenda called the ‘Big Four’.

[v] See https://africog.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/World-bank-Report-on-the-Standard-Gauge-Railway.pdf for main conclusions.

[vi] See https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2021/04/02/pr2198-kenya-imf-executive-board-approves-us-billion-ecf-and-eff-arrangements

[vii] World Bank, 2020, Systematic Country Diagnostic: Kenya, World Bank, Washington: DC.