I.

On Saturday 16 July I was robbed for the second time since living in Italy on the same train, the one that runs from Fiumicino airport into Rome. On both occasions I was targeted because I was travelling with children and had a lot of luggage. The first time I was with my pregnant wife and one child, going to Malaysia to start work on my last book, Asian Godfathers. This time I was returning from a month in China with my 8 year old daughter where I finished my latest book, to be published this year. This time I lost not only passports, wallet, laptop, etc, but also 500 pages of interview notes. The robbery was very professionally done, involving at least two people, and perfectly timed as the train reached a station. The Italian passenger next to me was also fully taken in. Money and cigarettes were dropped on the floor, and my daughter’s case moved, by one person, my rucksack grabbed from behind my daughter’s back by another.

The theft problem on the Fiumicino trains is endemic and could not exist without either the studied incompetence or the collusion of Italy’s railway police (Polizia Ferroviaria or Polfer). In 2004 I was robbed beneath a mass of video surveillance cameras on platform 26 at Termini station; I noted the location of the nearest cameras and the exact minute the robbery occurred; the police blithely said the cameras do not work. This time the theft occurred as the train arrived at Tuscolana station. A young policeman who helped me check bins around the station in the vain hope of finding my documents said on the subject of police collusion that he himself found it strange when recently transferred in to this unit that he was not asked to start out in plain clothes making some arrests on the trains; that, he said, is the norm in other rail police units; here, he was sent out on day one in full uniform.

When I took my daughter back to the station where we were robbed (the train had carried on to the next stop), we found the decoy (the ‘palo’) in the robbery sitting on a bench there. I asked him in Italian: ‘You were the person who dropped the money and cigarettes on our train, weren’t you?’ In front of myself and my daughter he said: ‘Yes’. He wasn’t afraid, didn’t try to run. When the police showed up he said he was just a builder catching a train (He was smoking a cigarette from the red Italian brand packet he had dropped before my eyes and showed the police the charger unit for an electric tool he had in his pack — with no tool). They searched him, said he had no prior form, and let him go. I gave him my phone number on a piece of paper, begging him to ask his accomplice to return the documents. That, really, is where Italy is at. You beg the person who robs you for some sympathy, because nothing else works.

Then we went to do the ‘denuncia’ at the Tiburtina police station. After 17 hours flying, and two hours of being robbed and looking for my documents, I rang the bell and the policeman who came to the door told us to come back in half an hour. I asked if we could wait in the waiting room inside. I had one credit card in my pocket, but no money, because four bank machines I had tried were out of order (the phone lines were down). The policeman said we could not come into the station and should wait in the street. When we returned, a policeman holding an i-phone, sporting an expensive watch and wearing spotless Sunday casuals launched into the preemptive statement about what a terrible place Italy is, how foreigners are mad to live here and how under-resourced the railway police are. Who can say, but he did not look to me like he works night and day catching thieves on the trains. Instead, he patronised my daughter: ‘Ciao, bionda.’ She is only eight, but she is already old enough to spot a certain kind of Italian man.

The policeman was insistent that I fill out a denuncia in English — instead of the standard Italian form — saying it ‘would be translated’, and despite my expectation and willingness to do this in Italian. As ever, you wonder why. Do the police really tell us how many people get robbed on that line? All we know for sure is that almost all the victims are foreigners.

Throughout this whole experience, my daughter and I were calm and accepting of our situation, including with the man who helped rob us. (My daughter cried very briefly at one point, for just about 30 seconds. She was trying to blame herself for the robbery because she asked to sit on the top deck of the train.) When I thought about this the next day, I realised that we have become the kind of people who accept suffering and unfairness as a part of normal life. In a sense, we have become Italian. The problem is — with the very greatest respect — I don’t want to be Italian.

II.

On 21 July I spent some time phoning around the railway police (Polfer) in search of published statistics about crime on the two Fiumicino train lines (to Termini and to Tiburtina). After some persistence I was put through to a woman who introduced herself as ‘Dottoressa Caccia’. Ms Caccia was the only person in my enquiry who was willing to give a name. (A web search suggests she is likely Barbara Caccia; like the vast majority of Italians who present themselves as ‘doctor’ she holds only an undergraduate degree.) Ms Caccia said that her office is responsible for Polfer statistics and, although my experience of being robbed twice on the airport lines was unfortunate, the statistical reality is that crime on the Fiumicino trains has fallen ‘at least 85 percent’ in the ‘last five years’. She was, however, unable to give me actual numbers, because she did not have them ‘sotto mano’.

After the robbery on 16 July, Gaia and I had to return from Tiburtina station to Tuscolana to see if my bag and papers had been abandoned (when we found the decoy sitting at the station) and then back to Polfer at Tiburtina station to do a denuncia. As we sat on our cases on these two trips, I watched at least two more pairs of impoverished eastern Europeans walking around the carriages in a manner wholly unnatural for actual passengers. Almost certainly they were looking for robbery victims. The policeman who took our denuncia said himself that we can have ‘no idea’ of the scale of theft on the line when he reflexively sought to defend the performance of Polfer. The helpful policeman who helped me look for my papers around Tuscolana station described the situation as running out of control, and said he understood that a member of parliament, whom he believed is from the Northern League, had been robbed on the train a few days previously.

There is no way that crime on these trains is down 85 percent. When I asked Ms. Caccia whether her numbers jived with reports received by foreign embassies about stolen passports, she pretended not to understand what I was saying and became defensive. ‘My memory is not perfect,’ she stated with respect to the data, telling me to write a request for figures on the state police ‘scrivici’ (write to us) web site. This site, I discovered, limits enquiries to 600 characters (about 100 words). None the less, I wrote a request, reassured by Ms Caccia’s guarantee that ‘If you write, we must respond.’

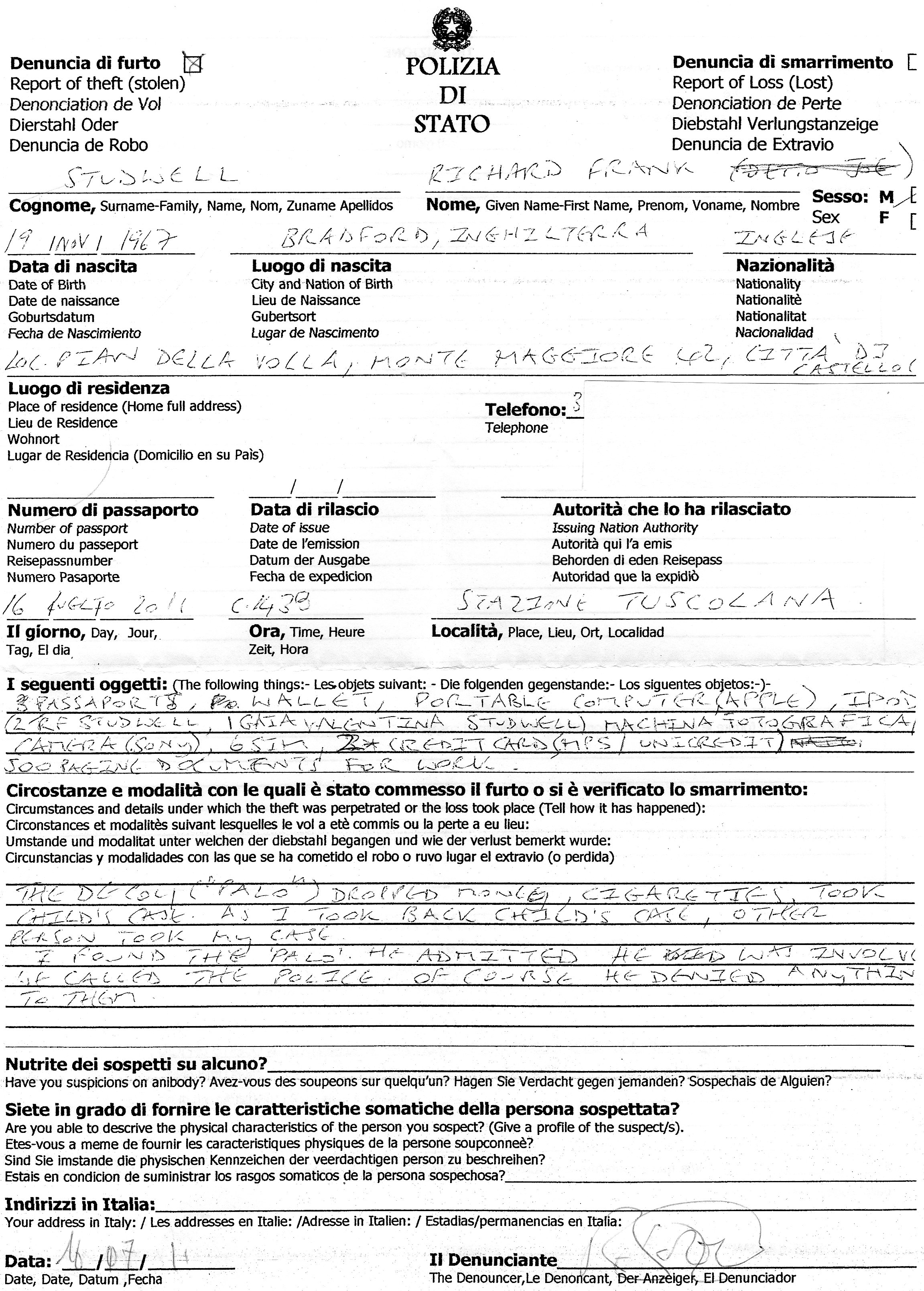

Thinking about Ms Caccia’s ’85 percent fall’, I looked again at the ‘foreigner’ denuncia that the officer at Tiburtina’s Polfer station had been so adamant I should fill out in preference to the standard Italian one. I realised what made me uncomfortable about the form: it contains no reference number of any kind. On Carabinieri denuncia forms I have looked at, there is always a ‘Numero protocollo Sdi’ and sometimes a ‘Numero protocollo Verbale’ as well. In other words the document is logged in ‘the system’. What I was made to fill out at Tiburtina station has no log in the system. It is simply a bit of floating paper, that could disappear without leaving any suggestion that it ever existed.

In addition, I note that at the top of the Polfer form are two small boxes to be ticked for either ‘stolen’ or ‘lost’. I missed these in filling out my form at the station. What then happened is that the Polfer officer photocopied my hand-written version, stamped a photocopy, and only ticked ‘theft’ on the copy he gave me. I very clearly watched him, through an internal office window, do the copying of the original and then bring a copy to me. I did not see him tick ‘stolen’ on the original or on any other copy, although he may have had me sign more than one copy. I cannot remember.

So. Is theft on the Fiumicino line down 85%? Or is reported theft down 85%?

III.

The problem with my mini-investigation is that checks with consular sections of embassies do not provide much useful evidence. The British embassy confirms it has had several thefts on the Fiumicino trains reported in recent weeks. But the US, Australian, New Zealand and Canadian embassies say that while they do have thefts reported on the trains, they see no particular trend. The Japanese say that the vast majority of thefts affecting their nationals at present are on Line A of the Rome Metropolitana (underground) on stops close to Termini station. While the Chinese say that most of their tourists come in groups and are rigorously warned by tour leaders about the risk of theft on Italian trains. (The Chinese embassy web site has descriptions of scams like the one that happened to us written up in great detail. There is also a description of an entire Chinese tour group recently being drugged and robbed on an Italian train. Of course all this is in Chinese… if stated in Italian, the content would likely lead to a minor diplomatic incident.)

What the consulates told me privately that they see does not add up to the industrial scale theft which I suspect goes on perennially on the airport trains. The reason may be that victims only turn to consulates if they lose their passports or all access to money, or both. And the vast majority of people are not as dumb as I am in keeping all their stuff in their back-pack. They have passports and credit cards closer to their person, in a wallet or pouch.

If I had not lost our passports on both occasions, it is unlikely I would have contacted the British embassy in Rome. After all, embassies are hardly places that invite extra business, and the British one in Rome is about as bad as it gets — one is told the (out-of-country) emergency number is for cases of death or equivalent seriousness, while the switchboard is only manned from 0915 to 1200 each day.

My first letter to the US embassy last week was met with a written response that any information about thefts on trains affecting US citizens ‘is police information held by Italian law enforcement authorities. We therefore suggest you to refer to the Italian Police/Carabinieri to get the needed information.’

The modern embassy/consulate is a pretty shameful institution, and robbery victims are sensible to avoid it unless absolutely necessary. So the one potential source of reliable information about the scale of crime on trains in Italy — and the Fiumicino lines in particular — is Polfer. Which brings us back to those new ‘foreigner’ denuncia forms with no serial numbers. I will pass this post on to various foreign embassies in Rome and see if anyone is interested. Hold your breath!

Exhibits:

The header of a standard Carabinieri denuncia form, with ‘protocollo’ serial numbers, is here.

The front of the foreigner denuncia form I was told to fill out is here. There is no serial number of any kind. This is the photocopy of the original given to me by the Polfer policeman. He has crossed the ‘Report of theft’ box at the top left, but he did not do this in front of me for the original or for other copies. (I have blanked out my phone numbers on this scan.)

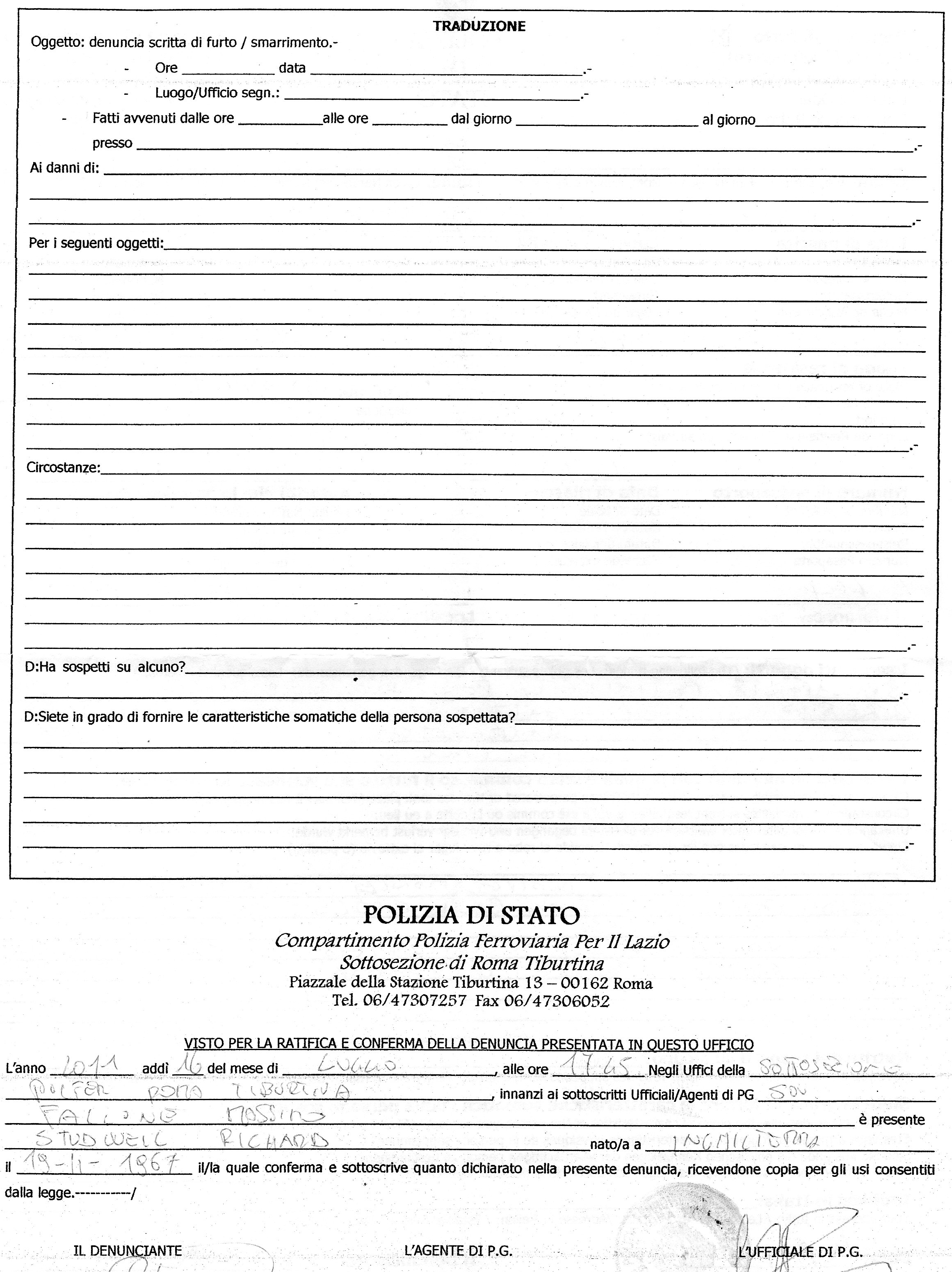

The back of the foreigner denuncia form is here. It is all ready for one of those Italian policemen who are fluent in foreign languages to bang out the translation and log the theft into the statistical record.