For some time I have been meaning to take a look at the structure of Italy’s public debt, and finally I did it. Let me assure you that the picture is every bit as ugly as one could imagine. I don’t mean the scale of the debt, which is known to almost every one. I mean the fact that Johnny Foreigner is totally, utterly on the hook. If this family goes down, we go down with them.

For the record, Italian public debt is currently around 124 percent of gross domestic product. Historically, this debt is the product of large, recurrent government deficits beginning in the 1970s. Over time, the debt load was compounded by the legendary ‘cunning’ (known in some cultures as ‘childishness’) of Italian politicians, manifested in manoeuvres like racking up the highest pension liabilities as a share of GDP in Europe — because it falls to another government, down the line, to pay the bill. So vote buying of one kind or another and a general willingness to mortgage the country’s future produced a large public sector liability.

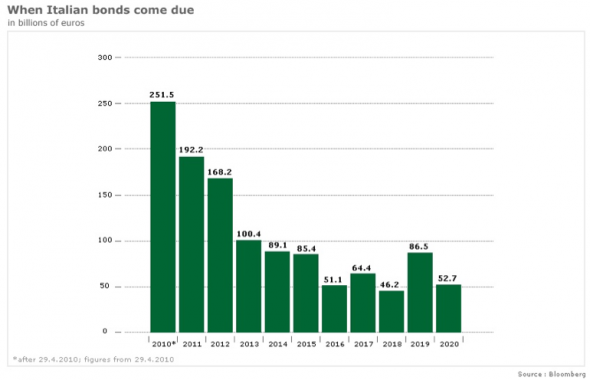

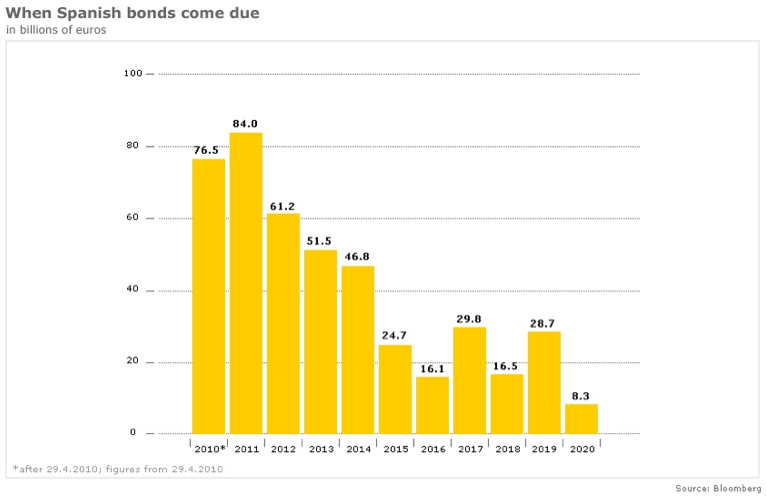

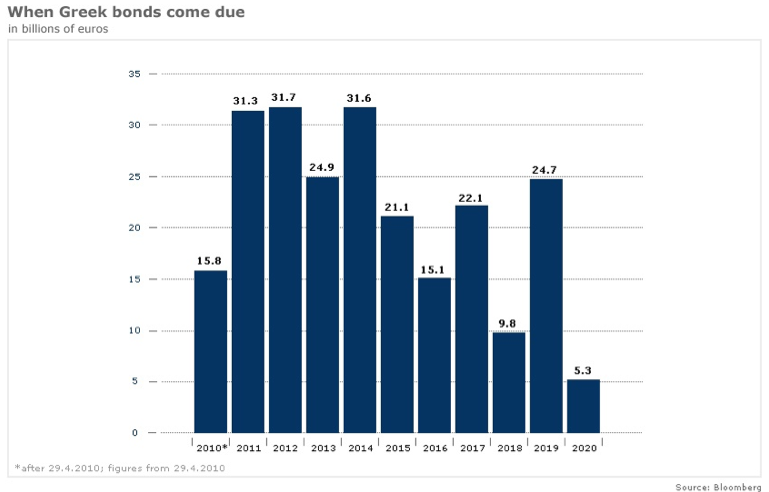

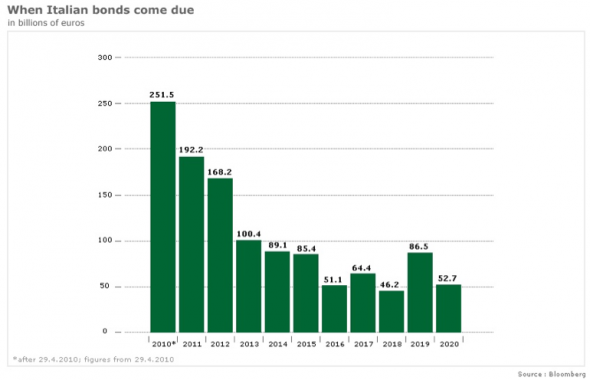

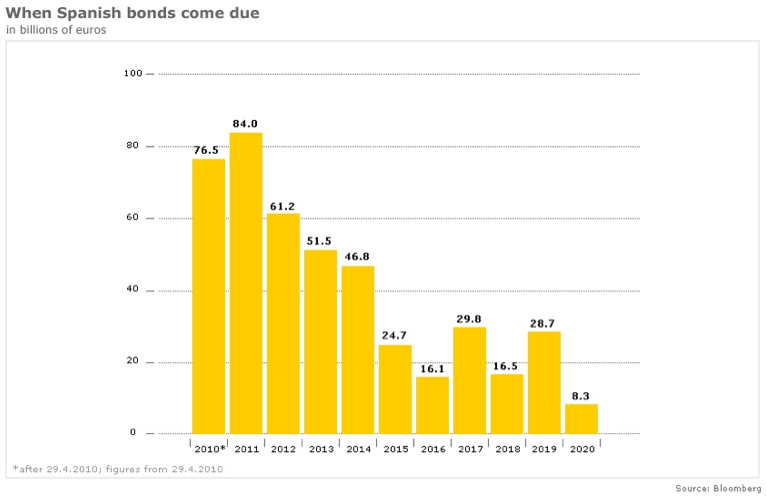

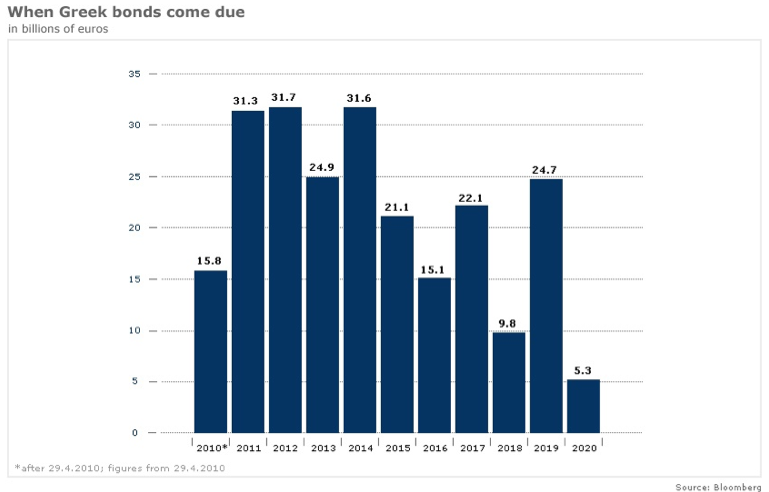

Next, because of Italy’s history of relatively high inflation, governments were only able to sell their debt by offering short maturities. The buyers of Italian bonds commonly insisted on stuff of less than three years’ maturity. As of this year, Italy has about Euro500 billion of debt — around one-third of GDP — coming due in the next 36 months, compared with the equivalent of less than one-fifth of GDP coming due in that period in Spain. Even Greece has a lower share of GDP coming due in the next three years than Italy. (See the charts below. Note that these data are already a year out of date — they are the most recent I could quickly obtain. As each of the countries rolls more debt over into future liabilities, the bars to the right will rise quickly…)

Before one freaks out about these numbers, you have to remember that debt is really an issue of capacity to pay. Greece has no capacity to pay, which is why the market has already written it off. Until recently, the market said Spain had less capacity to pay than Italy. But now Mr Market is re-thinking.

There is good reason to do so. Spain has an Anglo-Saxon problem. Its banks are bust because of excessive real estate lending — a private-sector debt problem. The solution, sooner or later, will be bank nationalisation followed by a fattening of bank spreads in a less competitive banking system. The raising of the spread between deposit and loan rates quietly socialises the cost of the bail-out without a full-scale political confrontation about who is responsible for the cock-up and who must pay (the people my Etonian banker friend calls ‘the great unwashed’). This is what is already happening in the US and UK. Real estate prices deflate and banks use fat margins on current business to offset losses on their historic mortgage books. It is a long and painful process, but ultimately the mechanism to pay for the banks’ greed and misadventure is relatively easy to put in place.

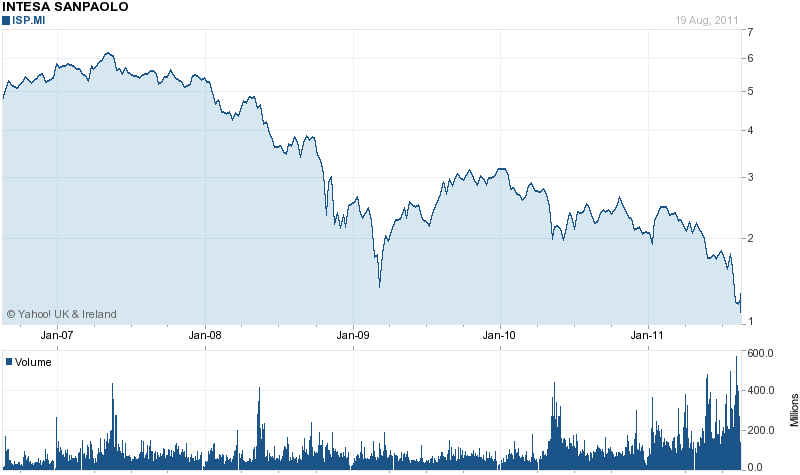

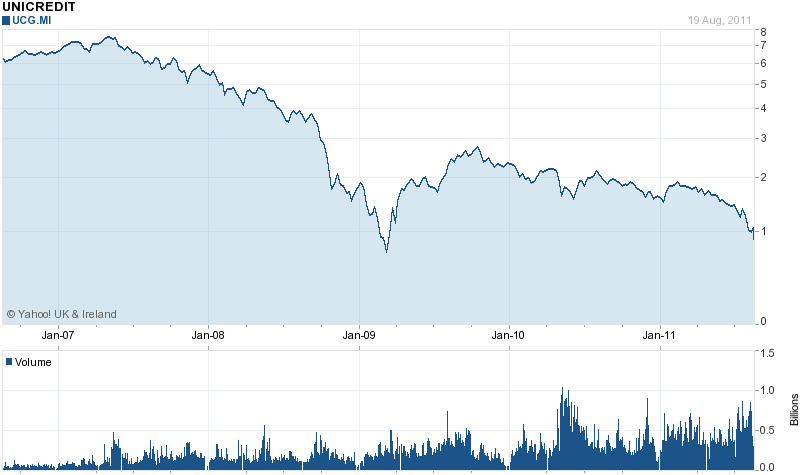

Italy is a different story. Its debt problem does not stem from a real estate bubble and banking excess. The banking system already restrains competition and banks have traditionally made good margin from lending conservatively. The problem of the Italian banks is instead that — partly as a quid pro quo for a protected, high-margin banking sector — they have been the domestic buyer of first resort of government debt. Domestic financial institutions hold the overwhelming majority of Italian-owned Italian government debt. Put another way, government has been bribing the population to acquiesces in its incompetence and inefficiency, and the banks have provided the funds to allow this to happen. It is a public debt problem, but the banks are are the private sector symptom of it. This is why the shares of Italian banks are getting hammered as the debt crisis deepens.

If you want a non-technical Italian analogy, the situation is as if Paulie Gualtieri had started a bank. The main business of Paulie’s bank is lending money to Tony Soprano so that Tony can buy Porsche Cayennes for Carmela, which keeps their troubled marriage from falling apart. This is a pragmatic arrangement, and Paulie and Tony regard it as very cunning. Of course, Paulie’s bank eventually runs into trouble. When this happens, there is no automatic mechanism to socialise the losses. Instead, Paulie and Tony have to go out on the street and raise new funds by ‘cracking heads’.

Unfortunately, this is where the analogy breaks down. Silvio Berlusconi may be hewn from the same moral block as Paulie Gualtieri and Tony Soprano, but he does not have the same resources in terms of soldiers on the street. Washed and unwashed alike lack ‘respect’ for Sil and his degraded lifestyle (some of them hark back to the days of the legendary capo Bennie Muss, but that ship has sailed…). Sil’s ‘family’ has been paring expenditure for several years since the global financial crisis broke. But his real problem is that the Italian economy has expanded an average of only 0.2 per cent a year since 2001. And the latest industry surveys suggest the economy is perilously close to contraction this year.

Put simply, there may not be enough money on the street for Sil to shake down, even if he had the wherewithall to do it. Mr Market knows this, and has pushed the price of Italian debt due for roll-over to more than 6 percent. When Greece, Ireland and Portugal exceeded a 7 percent cost of new debt, their bonds started to be sold off so heavily — because people no longer believed that they could be repaid — that bail-outs became inevitable. Italy may entering that arena and the symptom, as mentioned, is that Italian bank stocks are in precipitous decline. (Some of the more obvious investment advice today is: Short. European. Financial. Stocks.)

At this point, I know what you are thinking: the Sopranos had this coming. They’ve been taking the piss for years and, frankly, we’ve got bigger problems of our own to worry about.

Except that I am not sure that we do have bigger problems to worry about…

It is true that Italian banks hold most of the domestic share of Italian public debt. (Ordinary Italians have been far too sensible to load up on this toxic dross, despite any number of government schemes — mostly tax breaks — to encourage them to do so. The public holds only about 15 percent of Italian debt.)

However, apart from that held by Italian financial institutions, there is another vast chunk of Italian state bonds held by a different mob of wholly amoral financiers — foreign banks. Get this: approximately 900 billion euros of Soprano paper has been sold to foreign institutions, most of which represent a liability — if they go bust — to north European taxpayers.

Nine hundred billion euros is not some Greek, Irish or Portuguese morning after; it is a colossal, gob-smacking liability that means the Sopranos can probably make the rest of Europe jump through whatever hoops of fire they fancy. The line that Tony once used on Carmela is the one that Sil will likely use on the ECB: ‘Who knows more about extortion, me or you?’

Soprano-omics

Take a look at the aggregate numbers, displayed on top of the bars below, comparing debt due for roll over in Italy versus Spain…. (Greece, further down, is like discovering your kids failed to pay for half a dozen ice creams.)

|

2009 |

2011 |

| Japan |

218.6 |

231.9 |

245.6 |

| Italy |

115.1 |

123.5 |

128.5 |

| Greece |

113.4 |

126.8 |

— |

| Belgium |

97.9 |

104.9 |

— |

| United States |

84.8 |

97.7 |

108.2 |

| France |

77.4 |

86.6 |

92.6 |

| United Kingdom |

72.9 |

89.3 |

98.3 |

| Germany |

72.5 |

87.8 |

89.3 |

| Ireland |

64.5 |

87.9 |

— |

| Spain |

55.2 |

66.9 |

— |

| Sources: European Commission, IMF, OECD. |

Don’t let Japan, in the table above showing public debt as a share of GDP, make you feel better about Italy. Japan is a qualitatively different story because almost all its ridiculously large debt is financed by domestic borrowing. Indeed the willingness of the Japanese to pay for the debt at close to zero interest is what allows it to be so big. Italy, by contrast, plans to have its debt and then have foreigners pay for it. (The last column in the table above represents forecasts for 2014… for some reason the date will not reproduce.)

The thought to keep me awake at night:

In order to get out of jail, one Carnegie Endowment economist reckons Italy needs to achieve a primary budget balance (before interest payments) of PLUS-4 percent of GDP and cut real wages by at least six percent (to restore some competitiveness). Is this likely? After Italy joined the Euro in 1999, its borrowing costs were cut from a peak of 10 percent of government revenue before the Euro to under 5 percent because Italy was temporarily afforded German interest rates. This provided an extraordinary one-off opportunity to reduce public borrowing. What happened? Over the next 10 years, Greece cut public borrowing by more than Italy.

Also worth a look:

This recent European Commission study shows that, from 1998 to 2008, exports of goods and services grew more slowly in Italy than in any other member country.

Uncanny:

I post this, log on to the FT, and discover

this is the lead story (subscription needed).

Email, Print, TwittyFace this post:

Like this:

Like Loading...